February 9, 2011 — As American policy-makers grope for strategies to deliver broadly shared economic prosperity, calls for increased education are more insistent than ever. In his State of the Union address, President Obama drew applause by declaring that the United States needs to “out-innovate, out-educate, and out-build the rest of the world.” In that speech, and in a December address at a technical college in North Carolina where he outlined his economic vision, Obama repeated a pledge that he made upon taking office: by 2020, America will again have the highest proportion of college graduates in the world.

With these goals, Obama is taking up a “competitiveness agenda” that has been embraced, to varying degrees, by every American president since at least Ronald Reagan — in other words, since the twin pressures of technology and globalization began to reshape the economy. And it’s not only politicians who emphasize the importance of schooling: a recent National Journal article exploring the roots of the country’s current job shortage reported that nearly every economist interviewed for the story “called education a key piece of any solution.”

The importance of education to an individual’s earnings potential, and the value of public investment to promote education and innovation, is indeed one of the few things on which most economists agree. But a closer look at the actual experience of American workers in recent decades suggests that the message often implied by what might be called “the education answer” — that vast quantities of good-paying jobs are waiting to be created in new, scientific-sounding industries, and that a bachelor’s degree is the key to landing one of them — is woefully incomplete.

Some form of post-secondary education or training does seem to have become, as one recent report put it, “the only pathway” to a middle-class job. But if education has become a necessary prerequisite for economic success in modern-day America, it is hardly sufficient. And, a number of economists and other policy thinkers worry, by placing such an emphasis on the virtues of higher education, our policy elite is foreclosing discussion of alternative or complementary strategies that could deliver gains to many Americans — those with and without college degrees alike.

Male college grads “running just to keep in the same place”

Discussion of the performance of the American economy in recent decades often describes the rise of a “hollow middle.” The idea is that technology and globalization have eliminated — first in manufacturing, and later in business services — broad swathes of “mid-skill” jobs. This process, the thinking goes, created a polarized economy that puts holders of bachelor’s and advanced degrees — who have skills that are enhanced, rather than displaced, by technology — on one side, and workers with less education on the other.

But this account obscures an important fact: over a period of several decades, workers with only a bachelor’s degree have not fared particularly well. It’s true that the college-educated continue to do far better than those below them on the education scale, and that despite the rising cost, higher education is still generally a good investment. The so-called “college wage premium,” which rose sharply during the 1980s, persists; according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics covering the last three months of 2010, the average worker over age 25 with a bachelor’s degree but no advanced degree earned about 66 percent more than a high school graduate of the same age. And while unemployment spiked for all education groups during the current recession, mid-career holders of college degrees weathered the storm far better than most.

Relative to the experience of college graduates in the post-war decades, however — or to the expectations that they had for their own careers — recent generations of bachelor’s degree holders have seen disappointing results. After World War II, middle-class families from all education backgrounds saw steady income gains; the connection between a degree and a middle-class life today is in many ways rooted in the expectation that college graduates will continue to see such gains, even as those without a degree lose ground. Over the past decade, though, workers with only a bachelor’s degree have actually seen their real wages decline slightly, even as the cost of college has skyrocketed.

And these struggles are not only a function of the current downturn: the MIT economist David Autor wrote recently that “the real hourly earnings of males with a four-year college degree and no post-college education rose by only 10 percent between 1979 and 2007.” The growth in the college wage premium for men over that period, Autor wrote, was as much a function of declining earnings for those without college degrees as it was gains for those with them, a situation he described as “running just to keep in the same place.” (Women with bachelor’s degrees, while still earning less than men of equivalent education, made far greater gains — perhaps because obstacles that had previously held down their earnings began to disappear — as did advanced degree holders of both genders.)

Income inequality rising among college graduates

One explanation for this lackluster performance is that there is increasingly polarization not just between groups of workers, but within them. In other words, as the number of college graduates grows, there is greater variation in their experiences in the labor market.

Andrew Sum, director of the Center for Labor Market Studies at Northeastern University, has identified what he calls rising “malemployment” among the college-educated: essentially, degree-holders who are employed in jobs below their skill level, because the economy has not produced enough jobs in the “college labor market” — which Sum and his colleagues define as including “professional, technical, managerial, and high-level sales occupations” for which a degree is a necessary qualification. (Employers in other areas often prefer to hire college graduates when they are available, Sum said, but that does not make those jobs ones where employers treat having a college degree as a threshhold element of any application to be considered.) Turning a bachelor’s degree into a middle-class career, Sum has found, is almost entirely dependent on landing a job that is genuinely part of the college labor market. Graduates who manage that feat, on balance, are still doing fine; those who do not, earn scarcely more than a high school graduate while shouldering a rising debt burden.

And at present, an alarming number are failing in the latter camp. In 2010, according to figures compiled by Sum and his colleagues from government data, only about six in 10 employed college graduates under age 25 — and about half of all graduates in that age group — were in the college labor market. (African-American and Latino graduates are faring especially poorly; for African-Americans, one reason may be steep cutbacks in state and local governments, where more than one-quarter of black college graduates are employed.) Older workers do better, but even there, about one-quarter of employed bachelor’s degree-holders from ages 30 to 54 were not in the college labor market last year, according to the researchers at Northeastern.

While the Great Recession bears much of the blame for the economic struggles reflected in these data, Sum said, it doesn’t tell the whole story: young college graduates never fully regained the ground they lost during the last recession, which began in 2001. (He and his colleagues do not have malemployment data prior to 2000.)

Like others who study the labor market, Sum believes universities and students can both do better in terms of identifying and preparing for job opportunities. But the more fundamental problem, in his account, is a simple shortage of jobs in the college labor market. “There’s nothing that guarantees that supply [of college graduates] creates its own demand,” Sum said. “You’ve got to have more demand growth.”

The analysis of the Northeastern University center is not universally accepted. And while official projections from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that the greatest job growth over the next decade is likely to be in occupations that don’t require a degree, some other researchers expect the economy’s demand for college graduates to be strong.

But it would be hard to argue with the basic point that a college degree is a less certain (and far costlier) investment than it was a generation ago. “There are no safe haven positions, except for tenured faculty members and federal judges,” said Carl Van Horn, director of the Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University. “Everybody else is at risk, or needs to be responsive to this change.”

Is an innovation shortfall leading to a lack of jobs?

While the numbers indicate that college graduates are becoming more vulnerable — and so the “the education answer” is incomplete — those numbers can’t explain why that has happened, and what broad-based gains, if and when they return, will look like.

No consensus answer to that puzzle exists. One possibility is that changes in the structure of the economy have been so rapid that the demand for educated workers has steepened and sharpened — that, in effect, the advantages yielded by yesterday’s bachelor’s degree are today only derived from a master’s or Ph.D. In fact, advanced degree holders are the only class of workers who have seen consistent gains in real wages over the last decade (though there is increasing variation within that group, too).

Mike Mandel, an economist and blogger who is a senior fellow at the Progressive Policy Institute and Wharton’s Mack Center for Technological Innovation, has a different reply. In addition to technology and global trade, he points to another factor to explain sluggish wage growth: a shortfall in jobs-producing innovations.

The process of job creation in an industrial economy, Mandel said, is “a war,” with technology playing a dual role: technology-driven productivity gains squeeze out workers in existing industries, while innovations create new industries that demand higher-level skills. Since the 1990s, Mandel said, America has placed a bet that this job growth would come from biotechnology, genomics, and other advances in health — the U.S. government spends more on research and development in health than any other developed country, despite spending less on R&D overall — but that bet has yet to pay off. The result, he said, has been “an inexorable process… of squeezing.”

Mandel has some ideas on how to spur along innovation, such as applying a light regulatory hand to young industries like biotech. (He also has ideas for reducing the cost of higher education, and is the founder of a company that produces news and education videos designed to be used in online courses.) But his message is essentially one of patience and persistence, until the bet pays off. “Give me one blockbuster product,” he says, “and I’ll give you a much different labor market” — one that will reward workers with everything from an associate’s degree to a Ph.D.

“What’s left out of this in the journalistic accounts is sheer, naked power”

There are other ways to think about the role of technological innovation, however. Michael Lind is policy director of the Economic Growth Program at the New America Foundation, a nonpartisan think tank. Lind sees productivity gains from technology, rather than rising education standards, as the key source of economic growth, and a shortfall in such productivity gains as one of the causes of stagnation in recent decades.

But it is a mistake, he said, to expect large numbers of jobs ever to be created in the biosciences — or, for that matter, in information technology, our last great innovation. Rather, as technology continues to drive down the cost of basic goods and money is freed up for use in other areas, people start shifting their spending to a range of public and private amenities — everything from better health care, or more expansive public services (from enhanced after-school programs to nicer parks) funded by taxes, to simple quality-of-life gains like eating out more often.

This is part of the reason why health care, education, and government are increasingly large parts of the American economy and labor market, Lind said. And as businesses learn to make better use of the Internet, and existing business sector jobs are eliminated by the resulting productivity gains, the shift toward those fields will only continue, accompanied by growth in “high-touch” areas — he pointed to the latest BLS projections, which forecast the biggest gains in jobs like home health aide and carpenter — that are resistant to automation or outsourcing.

Some of these jobs will require substantial higher education; many others will not. But Lind is not troubled by that prospect — because he believes many factors beyond education shape an individual’s earning potential.

“We need to get away from the claim that low wages are the result of insufficient human capital,” Lind said. “What’s left out of this in the journalistic accounts is sheer, naked power.” He offers an alternative way to understand the impressive income gains for workers with advanced degrees, one rooted in their stronger institutional protections rather than the intrinsic value of their education: “If you smash the service workers’ unions and the manufacturing unions, but you leave the doctors’, the lawyers’, and the professors’ guilds intact, you get a more polarized society.”

If this account is correct, the economy of the post-war years is indeed gone for good. But what awaits us is far different from the vision often outlined by leading policy-makers. Presidents of both parties typically embrace, as Obama has done, the idea that most Americans will be competing in the global labor market in the future, and that to succeed they will need an ever-greater number of years of education. But “both of those statements,” says Lind, “are just wrong.”

Emphasis on education diverting attention from other policies?

Even observers who conclude that higher education will not be, by itself, the solution to stagnant incomes agree that there are gains to be made in that field. Many of the people interviewed for this story, while disagreeing about other subjects, emphasized that schools, policy-makers, and students themselves can do a better job of steering students toward the fields of study, and the occupations, that are most likely to deliver returns on an investment in education. Several spoke of the need to make internships and cooperative education programs — in which students spend up to six months working for a prospective employer — more central to the college experience. And all agreed that lowering barriers to college, and supporting public investment in research and education, were worthy goals.

There is also support among a range of policy thinkers for strategies to bolster skills training programs outside the classroom. Ideas in that vein include coupling unemployment insurance to mandatory retraining, or providing employer subsidies to support on-the-job skill development — an effort, Lind said, to move away from a status quo in which “the burden of guessing what the industry structure is going to be in 40 years is on the 18-year-old student.”

Still, the debate over what education can achieve is closely connected to far-reaching differences over policy, especially when it comes to helping workers who do not have degrees. In short: the more powerfully someone believes in the education answer, the less likely he or she is to support other strategies to boost wages or improve job quality.

Claudia Goldin is a professor of economics at Harvard University; along with her co-author Lawrence Katz, she has been a key voice arguing that a shortfall in educational achievement is leading to widening inequality. In a recent interview, Goldin called for stricter standards in education, but recoiled at the idea of interventions in the marketplace. “I don’t even understand what the labor market side of things can possibly do,” she said. “Make the American workforce a better workforce. And I’m not saying all will be solved, but we’ll certainly be better off.”

Goldin describes her conclusions as deriving from her research findings — “just the facts,” she said. But an emphasis on education holds natural appeal for analysts who approach the question of economic development and income growth with hostility toward labor market regulations or other interventions. Jason Fichtner, a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center, a free market think tank, explained in an interview last month that he and his colleagues were worried that growing inequality would lead to increasing demand for redistribution, regulation, and government services. Mercatus has begun to explore ways to improve primary education and expand college access, he said, as a way to “avoid those policies.”

Skeptics of the education argument take a very different view, embracing a range of policies from temporary wage subsidies during downturns, to support for unions, to a dramatically higher minimum wage.

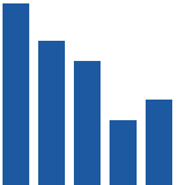

Their strategies reflect a belief that trade and technology may shape the mix of employment opportunities in an economy, but that the value assigned to those jobs is more fundamentally a function of a set of political choices. Lind, for example, supports a gradual increase in the minimum wage to perhaps $15 per hour. (The chart above shows the inflation-adjusted value of the federal minimum wage at selected points over the last four decades.) Such a move is consistent with his view that many of the jobs of the future will not require a degree, but that we can make them middle-class jobs nonetheless.

“Every labor market in every nation, including ours, is rigged,” Lind said. “It is a question of rigging labor markets in a progressive rather than a regressive direction.”

There is little space for that sort of approach in a policy regime that focuses only on education — and to critics of the education answer, that’s the problem. “Advocating for more education has always been the lowest common denominator that everybody can agree we ought to do,” said Lawrence Mishel, director of the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, who has written about the limits of education. “But what it really does, especially around issues of inequality, is avoid tackling the really tough questions.”