Poorly maintained gas pipelines put increasing numbers at risk

December 14, 2010 — A natural gas pipeline exploded Sept. 9 in the San Francisco Peninsula suburb of San Bruno, shooting a wall of fire hundreds of feet into the sky for more than 90 minutes as Pacific Gas & Electric utility crews had to fight rush hour traffic to reach manual shut-off valves, one of them more than 30 miles from the blast. The explosion — which left a crater 40 feet deep — killed eight people, injured 60 more, and severely damaged or destroyed 120 homes.

Many survivors in the surrounding area told reporters they had no idea that a 30-inch, high-pressure pipeline laid in 1956 ran through their neighborhood. Neither did city officials, says Mayor Jim Ruane, even though federal safety rules require that pipeline operators periodically alert residents to the presence of pipelines and train first responders.

Nationwide, pipeline blasts and fires kill a person every three weeks and burn or injure someone more than once a week.

Those are small numbers, as the pipeline industry emphasizes. But they reflect luck more than serious safety planning. As open spaces where pipelines were laid decades ago become developed, aging pipelines remain in use, and inspections have lagged, the risk of deadly blasts that can wipe out a block of homes, offices, stores or even schools and hospitals, grows.

As the number of people at risk increases, questions about the manner and scope of government regulation in this area become more urgent, as do questions about why the government has failed take a host of safety-enhancing actions recommended by, among others, the National Academy of Engineering and the National Transportation Safety Board.

Why, for example, do the Department of Transportation and its Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration rely so heavily on after-blast reviews, rather than on prevention?

Why do some key safety recommendations from the National Academy of Engineering and the National Transportation Safety Board gather dust? Among these are developing model land use ordinances and standard setbacks for construction near pipelines as part of a risk-based safety strategy, addressing potential damage to natural gas pipelines whose shipping may not have complied with safety rules, and requiring pipeline operators to have a system to calculate estimated release of gas or liquids.

Why has PHMSA not tightened its regulations over time, but instead granted safety waivers? Why doesn’t PHMSA focus on ways to improve detection of corrosion and other damage to pipelines? And why hasn’t PHMSA followed the Transportation Safety Board recommendation that it measure the effectiveness of mandatory notices to people who live or work in zones where a blast would result in certain death or injury?

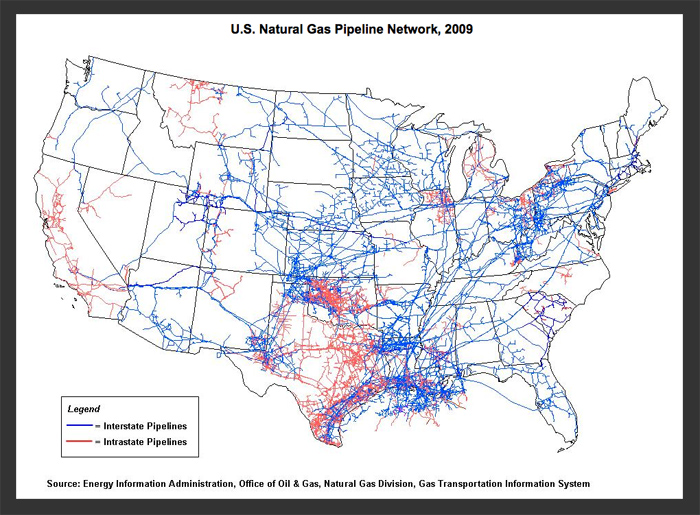

A massive network

There are three categories of natural gas pipeline systems, one of which poses much greater risks than the others.

The system with the fewest issues so far gathers gas at wellheads and takes it to processing stations. In Fort Worth and some other Texas towns, these gathering lines have begun to attract public concern, an issue that may increase with development of shale gas fields beneath and near cities and towns in Pennsylvania, New York, Colorado and other states.

The largest part of the system is distribution, the roughly 2.1 million miles of small bore pipes that carry natural gas to homes, offices and other buildings. Damage caused by backhoes and other excavation equipment is the largest danger here, but the risks are primarily to careless operators.

The potentially most dangerous system is the one linking gas gathering and gas distribution, the roughly 300,000 miles of pipelines up to 42-inches in diameter that transports gas long distances. The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration has jurisdiction over about 174,000 miles of this system. The rest do not cross state lines and are regulated by state safety agencies.