April 24, 2013 — Imagine this headline: “House of Representatives approves proposal for guaranteed annual income by wide margin.” The passage of that kind of social welfare measure sounds wholly implausible today, but, in fact, the House did pass such a bill in April of 1970 by a vote of 243 to 155. The measure, The New York Times reported, “establishes for the first time the principle that the Government should guarantee every family a minimum annual income.”

The story did not ultimately have a happy ending for advocates of guaranteed annual income (“GAI”) — the bill died in the Senate. But the fact that it received serious support and consideration in mainstream political circles is a testament to how radically the bounds of political debate have shifted since that time, and raises several crucial questions:

What allowed for GAI to be considered seriously by both Republicans and Democrats in the late-1960s and early 1970s? Why would the chances for a GAI proposal be so bleak today? And why are the answers to those questions critical to the outcome of virtually every other domestic public policy issue that exists today?

In the course of weeks of reporting — both through interviews and an exploration of the documentary record — Remapping Debate found that GAI proposals were given room to breathe in a social and political environment that took seriously the values of citizenship and mutual obligation, and that accepted the fact that social problems could be — indeed, should be — solved by governments.

That environment has disappeared, due in large measure, we found, to the rise of “market thinking,” a mindset that subordinated — and, in some respects, supplanted altogether — the values of citizenship and mutual obligation.

On both sides of the aisle, the voices describing unfettered market relations as a virtuous and unstoppable force to which the citizenry had to adapt and submit (as with globalization) grew ever louder. Ultimately, these market devotees drowned out those who continued to believe that government has a vital role to play and that markets do not on their own reflect and honor a broad range of important social values.

This article begins with an examination of the flowering of GAI proposals and the environment within which that process occurred. For those interested in jumping directly to a detailed exploration of the changes in dominant values that have effectively foreclosed not only the GAI, but other measures premised on the idea that Americans have a duty to care for one another, go here.

Providing basic economic security for all

To meet the challenge of “assur[ing] basic economic security for all Americans,” we need to make “cash payments to all members of the population with income needs.” So recommended a presidential commission in its 1969 report, “Poverty Amid Plenty: The American Paradox.” A family of four, for example, would receive a base income of $2,400 per year ($15,182 in 2013 dollars), with continued support for earnings up to $4,800 per year ($30,365 in 2013 dollars). Commissioners saw this as a “practical program” that could be passed by Congress quickly. (They estimated that the bill for the program would run to $6 billion a year, or $37.9 billion in 2013 dollars, a sum they considered a “relatively low dollar cost.”) In the longer run, they recommended “that benefit levels be raised as rapidly as is practical and possible in the future.”

As to whether people should be required to work to receive this income, the commission said “no.” Though “any program which provides income without work may have some effect on labor force participation,” such disincentive effects would not be serious, they suggested. Moreover, to the extent that “secondary family workers” or the elderly reduced work effort, such changes “may be desirable.”

In sum, the President’s Commission proposed that the United States adopt a version of a “guaranteed annual income” (GAI) — a method of ensuring economic security and dignity by means of the Federal Government providing money to any individual or family whose income falls below a certain floor, irrespective of whether the circumstance occured because of low wages, unemployment, prolonged illness, or disability. The commission came to this solution after concluding that forces beyond an individual’s control — not “some personal failing” — induced poverty. Thus, “the problem…must be dealt with by the Federal Government.”

The report’s solution may seem radical today, but it was part of a range of proposals in the 1960s and early 1970s that accepted the idea that a GAI would be an appropriate and effective way for the country to meet its obligations to citizens living in poverty. A year and a half earlier, in May 1968, over 1,000 university economists signed a letter supporting a GAI, and a similar proposal had also been floated by a panel of business leaders appointed by New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller.

The commission that made the 1969 proposal wasn’t even the first “President’s Commission” to recommend a GAI: the 1968 report of the “National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorder” (the Kerner Commission) beat them to the punch. And the 1969 commission proposal came five months after the Nixon Administration released its own, smaller-scale GAI proposal. In 1970, President Nixon’s version of a GAI passed the House of Representatives by a margin of 88 votes.

Though the specifics of such proposals — both in method of administration and level of support — differed considerably depending on the authors, “Among policy folks, academics, and activists…for a period of time there was consensus across the political spectrum that [GAI] was a pretty good idea,” said Brian Steensland, associate professor of sociology at Indiana University and author of the book, “The Failed Welfare Revolution: America’s Struggle over Guaranteed Income Policy.”

Support from very different sources

During the 1940s, conservative economists Milton Friedman and George Stigler had laid out the principles for a “negative income tax” (NIT). Each proposed to trigger government subsidy of a household when that household’s income dipped below a specified floor (the subsidy would have been designed to raise the household’s income to that minimum level), but at the time, the proposals were largely ignored.

Some on the other side of the political spectrum came to see a need for the GAI as well. In 1964, Michael Harrington, the socialist author of 1962’s “The Other America,” and other thinkers on the left wrote a letter to the President, Congress, and the Secretary of Labor arguing that, as automation continued to shrink the size of the workforce, income and work needed to be decoupled.

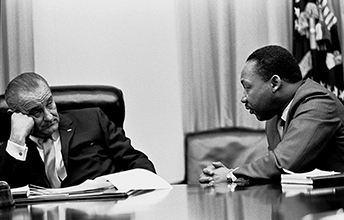

The “rediscovery” of poverty in U.S. — inspired in part by Harrington’s book and acted on by President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty — helped make the GAI a mainstream proposal by the end of the decade, as did critiques of the “welfare mess” emanating from activists and politicians across the political spectrum. (GAI was often synonymous with “welfare reform” during the Nixon years). Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), the program that had provided monetary subsistence mostly to single mothers with children was regarded as demeaning by many liberals due to its low benefit levels (which varied from state to state) and the fact that it reached no more than 30 percent of the poor. The same program alarmed conservatives because of its large bureaucracy, fears of creating a “dependent” welfare class, and concerns that the program’s structure encouraged the breakup of two-parent families (AFDC made it more difficult for a two-parent household to get aid).

A societal problem

If support for a GAI benefited from concerns across the political spectrum over what were seen as undesirable effects of existing programs, “The energy certainly was on the left,” according to Marisa Chappell, an associate professor of history at Oregon State University and author of the book, “The War on Welfare: Family, Poverty, and Politics in Modern America.” It was, Chappell said, “a moment when we actually see massive social movements demanding [changes].”

For example, in a 1967 book, Martin Luther King, Jr., a central leader in the civil rights movement, wrote that “we are wasting and degrading human life by clinging to archaic thinking” in failing to implement a guaranteed income. “A host of widespread positive psychological changes inevitably will result from widespread economic security,” King concluded. “The dignity of the individual will flourish when…he has the assurance that his income is stable and certain, and when he knows that he has the means to seek self-improvement.”

Implicit in the arguments for the GAI during the late 1960s and early 1970s was the sense that poverty was a problem that was the responsibilty of the broader society to solve. Senator Fred Harris (D-Okla.), for example, sponsored one “national basic income” bill, arguing as he introduced it in February 1970 that passage of a GAI would result in a “great moral dividend” for the nation. “It would allow us to feel,” Harris continued, “we are living more closely in line with the ideals we profess. We will more nearly be entitled to say that we believe in the dignity and value and worth of every human life.”

Harris’s sense that governmental solutions to social problems were both necessary and possible was not a minority position. Michael Katz, professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania and scholar of poverty and welfare in U.S. history, told Remapping Debate, “This was the era…when there were many new programs; where innovations in social policy that had seemed impossible had burst onto the scene and become plausible.” Citing the passage of Medicare and Medicaid (1965), the expansion of the food stamp program (1964), and the Fair Housing Act (1968), Katz characterized this historical moment as one where “the discussion of possibilities in social policy was much broader than it is today.”

The “possibilities” in social policy at the time indeed allowed ending poverty for all Americans seem, to Fred Harris, “not utopian.” The U.S. had already “made a strong beginning,” and Harris, the chairman of the Democratic National Committee from 1969 to 1970, said that the problem was only that “we have not carried our beginnings through their logical development.”

James Tobin, a former member of President Johnson’s Council of Economic Advisors who at the time was also a Yale professor, echoed this spirit in an article in The New Republic in 1967. Titled, “It Can Be Done! Conquering Poverty in the US by 1976,” Tobin argued for a GAI and believed that “if we seize the opportunity for a far-reaching reform, even at considerable budgetary cost, we can win the war on poverty by 1976.”

Guaranteed Annual Income legislation

In August 1969, in the eighth month of his presidency, Richard Nixon delivered a speech proposing the replacement of AFDC with a program that would benefit “the working poor, as well as the nonworking; to families with dependent children headed by a father, as well as those headed by a mother.” In case the point was missed, he continued: “What I am proposing is that the Federal Government build a foundation under the income of every American family with dependent children that cannot care for itself — and wherever in America that family may live.”

Guaranteed annual income had arrived. From the margins of economic thought just a generation earlier, the GAI was now at the heart of President Nixon’s domestic policy agenda in the form of the “Family Assistance Plan” (FAP).

Nixon himself refused to call the FAP a guaranteed annual income, saying that “a guaranteed income establishes a right [income] without any responsibilities [work] …There is no reason why one person should be taxed so another can choose to live idly.” But, despite Nixon’s rhetorical distinction, many conservatives opposed the president’s plan for just those reasons: they worried not only about cost, but also about the creation of a large class of people dependent on “welfare.”

Rhetoric aside, the FAP was indeed a form of GAI. The President’s Commission certainly thought so, writing in their letter submitting “Poverty Amid Plenty” to Nixon, “We are pleased to note that the basic structure of the Family Assistance Program is similar to that of the program we have proposed…Both programs represent a marked departure from past principles and assumptions that have proven to be incorrect.”

Nixon’s FAP was very moderate: it only applied to families with children (childless couples and individuals were out of luck), included a work requirement for householders considered “employable,” and would not have increased benefits for AFDC recipients in states providing relatively high benefit levels.

For a family of four without any other income, the FAP would provide $1,600 (2013: $10,121). But a family that did have income from employment would get a declining amount of FAP dollars until family income reached $3,920 (2013: $24,798). A family of four that had been earning $12,652 in 2013 dollars would have had its income increased through the FAP to $18,725. Ultimately, the vast majority of benefits would have gone to the “working poor,” a significant departure from then-existing programs that denied welfare benefits to those who were employed.

The FAP sailed through the U.S. House of Representatives comfortably, 243 to 155, but stalled in the Senate.

Many Congressional Democrats insisted that assuring the dignity of the poor required a more expansive program than the FAP, and criticized that proposal for its low income floor and work requirements. Representative William F. Ryan (D-N.Y.), who had been the first to introduce legislation for a GAI (in 1968), told the House in April 1970 that “accepting the concept of income maintenance and establishing the mechanics for implementing that concept are two far different things.” And though Ryan suggested “we do well to embrace the concept,” he characterized Nixon’s FAP as “seriously flawed.”

As an alternative, Ryan pointed to the proposal of the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO), which had argued for a much higher base income: $5,500/year (2013: $32,910). Ryan argued on the floor of the House of Representatives that:

[A] guaranteed annual income is not a privilege. It should be a right to which every American is entitled. No country as affluent as ours can allow any citizen or his family not to have an adequate diet, not to have adequate housing, not to have adequate health services and not to have adequate educational opportunity — in short, not to be able to have a life with dignity.

Come Home, America

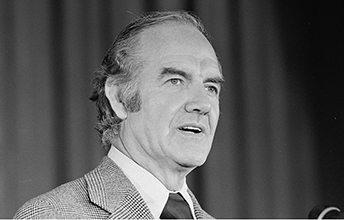

Nixon and Congressional Democrats, though, were not the only ones with a plan. In fact, the 1972 Democratic nominee for president — Senator George McGovern (D-S.D.) — rolled out his own GAI proposal in January of that year. McGovern suggested that “every man, woman, and child receive from the federal government an annual payment,” a payment which would “not vary in accordance with the wealth of the recipient” nor be contingent on the family unit. In contrast to Nixon, McGovern believed payments should be made to individuals and childless couples.

Drawing on his economic team, McGovern discussed a few specific proposals, including a James Tobin-inspired plan with a $1,000 per person minimum income ($5,554 per year in 2013 dollars), but emphasized that further study on configuring the plan would be necessary and “pledge[d]” that “if elected,” he “would prepare a detailed plan and submit it to the Congress.”

McGovern did begin to encounter criticism from some Democrats who suggested that he would be excoriated by Nixon for a proposal that, by some estimates, would subsidize 67 million Americans (almost 32 percent of the population). In the summer of 1972, McGovern shifted the focus of his policy proposals away from GAI and towards a full-employment agenda.

In August, McGovern presented what he called “national income insurance” to the public, a plan that would have provided “jobs for those who are able to work [through public service employment], a reasonable income for those who cannot work [$4,000 per year for a family of four, or $22,275 in 2013 dollars], and truly adequate Social Security” for the elderly and disabled.

Not entirely confortable with this formulation, McGovern added, “we must resolve the question of income supplements for working people who, in spite of their labor, still have trouble making ends meet. Even the unacceptable Nixon Family Assistance Plan recognizes the need to boost the income of those who earn too little.”

The candidate remained committed throughout the campaign both to the view that “our country lacks neither the means nor the will to meet the human needs of all of its citizens,” and to action that would have been at least the functional equivalent of a modest GAI.

Falling from favor

“If the Senate fails to act this year,” Senator Abraham Ribicoff (D-Conn.) told his fellow legislators in September 1972, “it is unlikely that the Congress will consider welfare reform at all in the next Congress, after years of fruitless effort already devoted to this subject. The tragedy of this failure will be more than a political one. It will be a human failure — a failure to help millions of Americans who subsist in poverty.”

Sen. Ribicoff’s sense of the politics was correct and a few days later, his final effort to pass the FAP failed, marking the highpoint for guaranteed annual income in the United States. Amidst calls for his impeachment, Nixon officially dropped the plan in his 1974 State of the Union speech. He resigned that August.

Beginning in the mid-1970s, a number of rapid political and economic changes wracked the U.S. Oil shocks, high inflation, and unemployment each challenged the assumptions of abundance that helped provide political space for pro-GAI arguments. In the mist of this economic and psychological turmoil, the values that had nourished support for the GAI — rooted in a sense of mutual rights and obligations between the country and all its citizens — began to be supplanted by those that emphasized the overriding importance of unfettered markets and individual gain.

Though President Jimmy Carter did revive another very moderate GAI scheme as part of his “Program for Better Jobs and Income” in 1977, the plan never got out of congressional committee. Other changes during the Carter Administration, however, including the deregulation of commercial aviation and trucking as well as the backing away from national health insurance and full employment programs, presaged a sea change.

The decline in support for guaranteed income “is in many ways reflective of the bigger story of the changes in values” in America, said Michael Katz, of the University of Pennsylvania. “[Guaranteed income] was a victim of a much larger paradigm shift that affected every sphere of society.”

By Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, the country in which GAI had seemed mainstream a decade earlier looked considerably different.

Part 2 of this article explores the changes in dominant values that have effectively foreclosed not only the GAI, but other measures premised on the idea that Americans have a duty to care for one another. What happened to citizenship and mutual obligation? Continue reading here.