Looking beneath a consulting firm's facade of objectivity

Price also pointed out that the report mentions recently negotiated autoworker contracts as an example of flexibility. Remapping Debate has previously reported on how the two-tier contract agreed to by General Motors and the UAW compares with data going back 50 years on autoworker compensation and how the two-tier system — originally presented as a temporary arrangement — has an impact on the lives of second-tier auto workers.

Win-win or win-lose?

Map & Data Resources

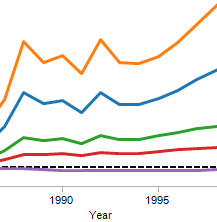

As the highest income households have increased their share of national income, real wage of production workers have stagnated.

Price said that now that two-tier agreements “are a feature of the times, a lot of the talk about flexibility has referred to the fact that even in Northern states, unions are willing to make concessions.”

Revisionist history

The report contains a short, four-paragraph history of the decline of manufacturing in the United States since the 1950s. It describes a dramatic shift of manufacturing to Asia in the 1970s and 1980s, but then provides an upbeat telling of the changes that followed.

“The U.S. suffered through many painful adjustments to these challenges,” the report says. “Unlike most nations, however, it quickly ripped off the Band-Aid and allowed industry to adapt. Factories closed, companies failed, banks wrote off losses, and workers had to learn new skills. But U.S. industry and the economy responded with surprising flexibility and speed to reemerge more competitive and productive than ever.”

According to Price, the wording of the report implies that all sectors of the economy — factories, companies, banks, and workers — suffered equally when manufacturing moved offshore. “Workers had to do more than ‘learn new skills,’” he said. “Yes, most of the manufacturing workers who lost their jobs got new ones, but they were jobs that paid less. There is a persuasive literature that says that when there is a mass layoff, the cost of dislocation is quite severe. It’s even been shown that [going through one] knocks a year off your life.”

BCG’s narrative is not the whole — or the accurate — story, Stein agreed. “There is still a whole class of workers that is suffering from that period today.”

Stein also took issue with another, implicit aspect of the history: the assumption that offshoring has been — and will continue to be — the unavoidable result of the “natural” process of globalization. The report, she said, glosses over policy choices that have been made in the United States and other countries to promote free trade and offshoring.

“I think this report was done for ideological reasons,” she added. “The ideology here is that we can all stop worrying, because the market is taking care of it already.”

And according to Price, the idea that, due to market forces, the overall economy recovered after a period of adjustment is misleading. “It’s true that we’ve undergone a transformation,” he said. “But it’s not a rosy one. The real story is less about everyone recovering than it is about certain sectors getting creamed and an overall economy that hasn’t performed very well for anyone below the top five percent.” (See graph above.)

What about McKinsey?

Several experts said that McKinsey & Company, described on its website as a “global” management consulting firm that “strive[s] for world-shaping client impact,” has been extremely influential in pushing for policies that promoted offshoring. According to Bob Baugh, the executive director of the AFL-CIO Industrial Unions Council, McKinsey created an entire department — the McKinsey Global Institute — in order to sell the benefits of offshoring.

“They had a whole shop where they put out this literature,” Baugh said. “This was a very clear example of how the transnational financial community has driven decision-making on offshoring.”

In 1994, McKinsey published The Global Capital Market: Supply, Demand, Pricing and Allocation, a paean to the virtues of globalization, one that, like reports that followed, subordinated other values to what the firm saw as the prime virtue: the unencumbered movement of capital.

A global capital market, if nurtured properly, would “create a happy outcome for the world,” the report said.

According to McKinsey, that global market would, “impose strict discipline on all participants,” requiring governments in the developed world, among other things, to address immediately what it called “unsustainable social obligations.”

McKinsey warned governments not to take actions “unattractive to the market.” They are not, for example, supposed to “issue excessive debt or over regulate financial systems.”

A key feature of the report was the attempt to persuade policymakers that the global capital market is and ought to be beyond their control, and that, rather than trying to make the market adapt, governments need to submit to it.

“It does not matter whether or not a national government or a particular political party likes or dislikes the development of such a powerful global market and the loss of direct control of its domestic financial economy any more than whether or not a national government likes or dislikes nuclear weapons,” the report says.

McKinsey’s own introduction to the public policy report makes its intentions clear: “[W]e will describe why a national government has no choice but to move forward to embrace the global capital market unless it wants to harm its own citizens, its economy and its own purposes.”

This market is given an awesome creation myth: “What has been done cannot be undone without truly destructive consequences. No one designed this global market. It came into being as the result of millions of individual [investor] decisions…despite all of the physical risk and regulatory barriers that originally limited the markets’ existence.”

To McKinsey, the perfect global capital market would be one in which capital would flow and prices would be set “through the natural self-interest of all participants without regard to national boundaries.”

McKinsey said that when a government attempts to shape or control capital flows — what the report calls “distorting” those flows — it “almost always causes problems,” and that, “In general using regulation to prevent the spread of financial innovations (e.g., securitization, derivatives), and/or to protect existing institutions, will also hurt the nation’s long-term interest.”