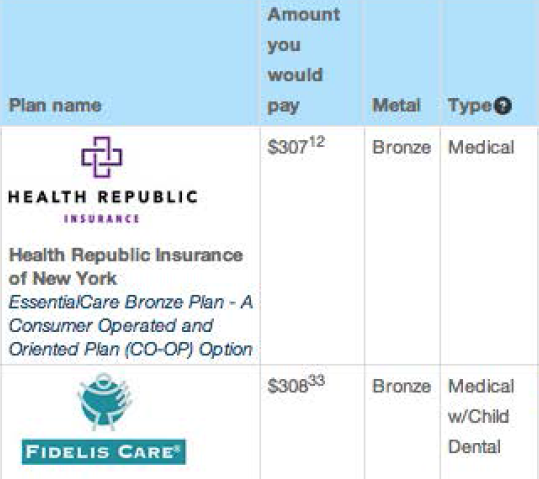

Oct. 30, 2013 — New York’s health insurance exchange (called “NY State of Health”) offers individuals and families numerous insurance plan options at various “metal” levels. What it doesn’t offer in most parts of the state are plans that provide coverage for non-emergency out-of-network care. In a sample Manhattan zip code, for example, there are 62 plans available at all metal levels. Not one of those plans pays for out-of-network care (see graphic).

This outcome is not a “glitch,” a State Department of Health official has confirmed to Remapping Debate. Instead, it is a function of New York’s decision to permit insurers to elect whether or not to sponsor plans that include out-of-network coverage. That decision, some worry, will have a negative impact on patient choice and patient care.

“We left it up to the insurers”

Out-of-network coverage had, until recently, commonly been available via employer-based plans (albeit with ever-increasing deductibles and co-payments). And a state establishing an exchange pursuant to the Affordable Care Act certainly has the authority to require coverage of out-of-network physician services. Indeed, in the small business part of the exchange (“SHOP” plans), New York requires a participating provider to include a plan with out-of-network coverage if it offers such coverage in the commercial insurance market (see bottom box for the limitations of that policy). But, on the individual and family side, the state decided not to use its authority.

Randi Imbriaco, director of plan management for the Department of Health (DOH), said she didn’t think anything was lost by not having an exchange option for individual and family plans that provides out-of-network coverage. Pointing to a process of state review of each plan for access to and adequacy of both specialists and primary care providers, Imbriaco said that insurers are required “to allow their members to go to the out-of-network provider” if “there’s a specialty lacking or they don’t have enough providers.”

Mo Auster, the vice president of legislative and regulatory affairs for the Medical Society of the State of New York, a physician advocacy organization, said that the lack of a requirement to cover of out-of-network care would reduce patient choice and increase insurance company leverage.

Mark Scherzer, a health insurance attorney for patients and legislative counsel to the advocacy organization New Yorkers for Accessible Health Coverage, characterized the absence of the requirement as a lack of a “fundamental consumer protection,” and asserted that the theoretical right to go out of network when there is not an “appropriate” in-network provider is enormously difficult to achieve in practice. The burden of proof, he said, is on the patient, and it is not enough for the patient to show simply that her out-of-network choice would be better.

If “you have a choice between a doctor who’s in the network who has done the procedure you need done three or four times and who is board-certified in the specialty that typically treats your disease, your plan is going to say that person is ‘appropriate,’ even though there may be someone down the street, who is out-of-network, who does 20 of these procedures a week and is a recognized expert [and with whom] it’s going to be far safer for you, far better outcomes for you. But the burden on you to get to that person is to prove that the person in the network is inadequate for your needs…And that’s a really hard case to make.”

Why then did New York State not require out-of-network coverage? “We left it up to the insurers,” said DOH’s Imbriaco, and the insurers, she continued, arguing that “a closed network helps keeps costs low,” chose not to provide out-of-network coverage in most of New York State, including New York City (some plans in the western part of New York State do offer such coverage).

Wouldn’t it be a useful option for New Yorkers to be able to select a plan with out-of-network coverage, even if that plan were more expensive than one without such coverage? Imbriaco had the same answer: “Well, that was a choice made by the insurers, and they decided not to.”

Increased leverage for insurance companies

The Medical Society’s Mo Auster said that the idea that insurance companies and individual doctors engage in a genuine negotiation — whether concerning fees or medical decisions — is a fiction. Since the insurer’s terms are “pretty much ‘take it or leave it,’” he said, a doctor’s only influence over the process was his or her ability to run a practice without signing up with a network. “The extent to which that ability is minimized,” Auster said, “further enhances the negotiating leverage of the health insurance company to basically take the clinical control away form the doctor.”

Dr. Andrew D. Coates is an internist based in upstate New York who is president of Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP), an organization that advocates for a single-payer health insurance system. Coates, who was speaking during the interview for himself and not as a representative of PNHP, agreed with the idea that the lack of out-of-network options would enhance the ability of insurance companies to engage in cost cutting, regardless of whether patients were harmed, as, for example, in a push for doctors to see more and more patients each day.

He thought that doctors were increasingly being put in an “ethical bind” where their medical instincts might tell them in a particular instance to recommend an out-of-network physician — the “one oncologist that you can think of that should really evaluate what to do next” in the case of a rare cancer — even as they knew that following that recommendation would be financially ruinous for the patient.

More broadly, in Coates’ view, the greater empowerment of insurance companies was accelerating a turn towards “a corporate medical model that threatens to squeeze the humanity out of our interaction with our patients.”

Remapping Debate asked Imbriaco whether DOH was concerned about doctors not having sufficient leverage to negotiate the terms of their services with insurance companies. “We try not to get involved in the negotiations between insurance companies and providers,” she replied. “The only time we get involved is when consumers end up being put in the middle of this feud. And then we try to talk to the two of them to work it out.”

Imbriaco did agree with the premise that only having to deal with in-network doctors makes it easier for insurance companies to control their costs (and, conversely, that having to cover out-of-network care makes it more difficult). She said that, from the point of view of the marketplace, more cost control was a good thing, describing the closed networks as a “contributory factor” to what New York is touting as a 53 percent reduction in individual market premiums from their current, pre-exchange rates. (“We’ll see,” Imbriaco noted as a caution elsewhere in the interview, whether the closed-network-keeping-costs-down theory “actually plays out the way it’s supposed to.”)

Could “the marketplace” have done better?

Bill Schwarz, the director of the public affairs group for DOH, participated in the interview with Imbriaco, and later clarified in a follow-on email exchange that the principal reasons for the large reduction in individual market premiums from pre-marketplace status quo are an anticipated more than 36-fold explosion in the size of the individual market (from 17,000 to a projected 615,000), making for an enrolled population that is, on average, healthier.

Schwarz didn’t, however, answer two of Remapping Debate’s inquiries made in the course of that follow-on email exchange: Isn’t getting rid of out-of-network coverage a material factor in cost reduction? And, if not, why not have required insurance companies to provide plans with an out-of-network option?

Notably, the small individual market in New York had until this year required insurers to provide out-of-network coverage, but the market had faced one species of “adverse selection,” the problem attracting primarily the sickest people. In New York’s individual market, Mark Scherzer said, there was not adverse selection of one carrier as compared with others (since all were required to participate) but rather of the entire market. Scherzer attributed the adverse selection problem to the fact that New York had “a voluntary market, which took sick people and didn’t give anybody else the financial capacity to participate. And that’s what the Affordable Care Act is supposed to resolve.”

What if New York had required out-of-network coverage as the price of admission to a new pool of almost 600,000 projected enrollees? Scherzer said, “There was no imperative” to remove the requirement of out-of-network coverage. On the contrary, he said, it would now “not adversely affect the market to require that.”

“It has adversely affected the market up ‘til now to have generous benefits that sick people could buy only because the sick people were the only ones who bought it,” said Scherzer. That’s no longer the case. Now we have a mandate for everybody to buy it. So you’ve eliminated the problem that [the insurance companies were] running away from.”

Scherzer’s conclusion: “What a stupid time to eliminate the consumer protection.”