February 16, 2011 — The shortage of doctors in the United States — already a problem for millions of Americans who live in areas where it is difficult to get an appointment or access to emergency care, and millions more who suffer long wait times only to have abbreviated visits with their physicians — is almost certainly going to become much worse over the next 10 to 20 years.

Having failed to increase medical school or residency slots significantly in recent years, the U.S. — with a still growing and fast-aging patient population, and now face-to-face with an impending wave of physician retirements — is poised to suffer even more serious physician shortages in the next decade, with estimates ranging from 90,000 to 200,000 fewer doctors than will be needed.

And because it takes a very long time to yield new doctors from any policy decision aimed at increasing the number of doctors being trained in medical school and the number of residency positions at which those medical schools graduates can get their post-graduate training, the window within which Congress and the medical community can act to avert the onset of a serious shortage is closing rapidly.

Nevertheless, efforts to increase the physician supply in recent years have met with opposition from members of both political parties, and even from some segments of the medical community itself. The result has been a sustained political logjam, leaving advocates worried that before the political will to address the problem develops, the consequences of inaction will be all too apparent.

Physician and patient demographics

Whether considering the projection from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) of an overall physician shortage of more than 90,000 by the year 2020, or the 2009 report prepared on behalf of the Physicians Foundation put that number at 200,000 by the year 2025, it is not difficult to understand the fundamental reasoning behind these numbers.

First, the number of new physicians entering the workforce each year has not increased dramatically for over two decades.

Second, the U.S. population has been growing substantially — from less than 250 million in 1990 to more than 300 million today, and to a projected 357 million in 2025 and 439 million in 2050.

Third, the number of people over the age of 65 is rising sharply — from about 31 million (12.6 percent of the population) in 1990, to a projected 64 million or so (17.9 percent of the population) in 2025. According to the AAMC, those between 65 and 74 use health care services at a rate more than twice that of those under 65.

Finally, the pool of working physicians is about to decline dramatically. Currently, there are about 800,000 doctors practicing in the United States. And those doctors are getting older and will be retiring in massive numbers. The AAMC estimates that approximately 250,000 physicians will retire within the next ten years — nearly one-third of all physicians.

In other words, in the next 10-15 years, the U.S. will have many more patients, a greater percentage of whom will need more medical care. Without more new physicians entering the workforce than there are older physician retiring, there will be fewer doctors to care for all those patients.

Consequences for patient care

According to George Sheldon, the director of the Health Policy and Research Institute of the American College of Surgeons, as the physician-to-population ratio falls, current healthcare access issues will likely be exacerbated. Sheldon said that the shortage will be felt most acutely in rural communities, many of which already face healthcare access problems.

In metropolitan areas, where there is a greater concentration of doctors, the shortage will likely translate to longer wait times and a larger burden on individual doctors, and could also eventually lead to problems getting a appointments, added Richard Cooper, the former dean of the Medical College of Wisconsin who has long warned of the physician shortage.

Recent surveys of patients receiving care in urban areas show that appointment wait times have already increased in the last five years. Other reports show that the average length of a primary care appointment in 2009 was just 20 minutes, and that family physicians see nearly 17 patients per day, on average.

Christiane Mitchell, senior legislative analyst for the AAMC, also foresees these problems getting worse. “You’ll see a lot more people who can’t get access to care. You’ll see people who can’t get appointments, and you’ll see doctors having to take on more patients,” she said.

A long pipeline

Because patients will be showing up in record numbers just as doctors will be retiring in record numbers, it appears that minor boosts to physician supply would be wholly inadequate. According to a report issued by the AAMC, “even a moderate growth in supply requires substantial inflow to replace the substantial number of currently practicing physicians who will be leaving the workforce in the next 20 years.”

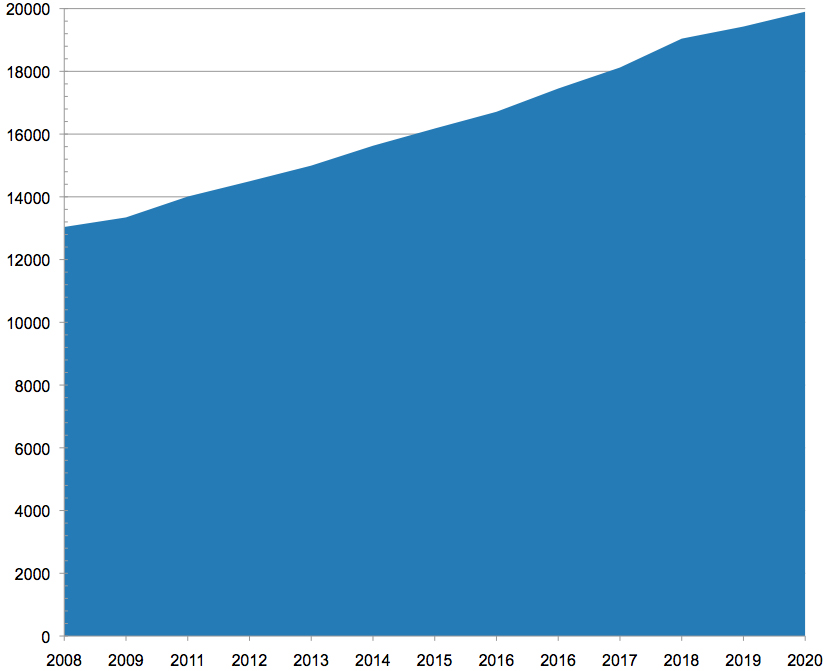

To put the matter in context, U.S. medical schools only graduated 16,838 students in 2010, a relatively small increase compared with the 15,676 graduates in 2002, and a pittance in view of the coming demographic storm. (Indeed, the number of medical school graduates in the U.S. is not sufficient to fill the residency slots available, which meant that, in 2010, 20 percent of the applicants matched to first year residencies were educated abroad, according to the National Resident Matching Program.)

The process of increasing the physician supply takes time, and is complicated by multiple hurdles. Most advocates agree that the first step is to expand the number of medical school students, both by increasing enrollments at existing schools and creating new ones.

In 2006, the AAMC set a goal of increasing medical school enrollment by 30 percent by 2015. Enrollments at existing schools have expanded modestly, and, in recent years, nearly two-dozen new medical schools have opened or are in the process of being accredited. (It generally take years for these schools to begin operating at full capacity, however. Even then, it is likely that, in the aggregate, they will only graduate several hundred more students each year.)

The result of these efforts so far has been relatively small increase in enrollment — from 2006 to 2010 the number of students enrolling in U.S. medical schools increased by 7.5 percent.

But that increase — or a greater one — won’t necessarily translate into more doctors. In order to become practicing physicians, graduates must complete at least three years of residency training, usually in large teaching hospitals. Without more residency slots, the number of physicians entering the workforce cannot increase. (If the number of U.S. medical school graduates increased, but the cap were left in place, graduates of U.S. medical schools, who have preference for residency slots, would replace graduates of foreign schools, but that would have no net impact on total physician supply.)

Logjam in residencies

The logjam in residency openings stems from the 1997 Balanced Budget Act. At that time, the number of residency slots funded by Medicare (the principal source of residency funding) was capped at around 100,000, and that cap has remained in place ever since.

Since the cap was set in 1997, there has been a slight increase in the total number of residency positions. Experts say, however, that most of these new positions — which are usually funded directly by the teaching hospital — are not first-year residencies, and cater instead to advanced training in specialty medicine.

Michael Whitcomb, who has served as the dean of a number of medical schools and has also worked for the AMA and the AAMC, said that “the determinate factor of physician supply in this country is the number of entry-level positions in the country’s graduate education system.”

But George Sheldon identified another obstacle. Even if the number of residency positions funded through Medicare were increased tomorrow, he said, the current infrastructure at teaching hospitals wouldn’t be able to handle a large number of new residents.

“We have examined how much expansion we could have in existing [residency] programs, and it’s not a whole lot,” Sheldon said. “Now we’re starting to look for places that aren’t currently doing training, and see which ones might be made available to do it.”

Whitcomb agreed that, within the current infrastructure, it is unlikely that there are enough hospitals willing to take on the training associated with the increased residency slots required to maintain the current physician-to-population ratio.

“No matter what we do, we are going to end up with a shortage of physicians in the next decade, which will grow progressively worse if nothing is done now,” Whitcomb said.

“It may well be that we can’t keep up,” Sheldon added, “but we haven’t even started. It may well be we can’t solve the problem, but I don’t think that’s a reason to believe we shouldn’t try to.”

The government’s role

Every step of the process of increasing physician supply requires some action on the part of state and federal lawmakers. Most new medical schools require state funding to open, and many are opened as part of existing state universities, like the University of Central Florida and Texas Tech University, both of which have started medical schools with “preliminary accreditation” status.

Large increases in medical school enrollments in the past have also been funded by the federal government. In the 1960s and ‘70s, enrollment at U.S. medical schools more than doubled, largely due to funding from the 1963 Health Professions Education Assistance Act, which provided grants for the construction of new facilities and the expansion of existing schools. This action was a direct response to two reports issued by the Office of the Surgeon General in 1958 and 1959, both of which predicted a coming shortage of physicians.

The two-decade expansion in medical education stopped in the early 1980’s because government reports at that time predicted that the U.S. would experience a surplus of physicians by the year 2000. New medical school expansion halted, and in 1997, Congress passed the Balanced Budget Act, which limited the number of medical residencies that could be funded through Medicare to the 1996 level.

At that time, there was a broad consensus in the medical community that the education system was producing more physicians than were necessary, and the limits placed on funding were supported by the AAMC, the American Medical Association, and the Council on Graduate Medical Education (COGME).

That consensus broke in the late 1990s, when Richard Cooper and a handful of other physicians and researchers began to question the projections of a surplus. In 2002, Cooper published an influential paper that raised doubts about the previous projections.

“Everybody was saying that by 2000, there would be this huge surplus of physicians,” Cooper said in an interview. “That didn’t happen.”

In the following few years, the AAMC, AMA, and COGME all reversed their positions after largely adopting Cooper’s model. In January of 2005, COGME released a report that deviated from its previous position by projecting a physician shortage, and recommended a “multi-prong strategy” that included increasing the number of physicians entering residency training by 3,000 every year for 10 years.

According to Cooper, however, the “political headwinds” at that time were just too strong, and none of the groups had the desire to push very hard against them.

“Even as the body of evidence for a shortage was growing,” he said, “the government and people in the medical field were still debating those projections.”

According to the AAMC, congressional resistance to their proposals was budget-related. The AAMC’s proposals would have cost $10 billion over 10 years.

“Whenever we would approach the [House] Ways and Means Committee, they would look at us and say, ‘That’s a lot of money,’” said Christiane Mitchell, senior legislative analyst for the AAMC. “They were not convinced about the severity of the issue.”

The Dartmouth perspective

Though there has been a growing consensus in recent years among medical advocacy groups and some members of the government that a shortage is imminent, a small but vocal group of critics in the medical community has continued to argue against proposed increases in physician supply. Most notably, research conducted by the Dartmouth Institute of Health Policy and Clinical Practice on physician distribution and medical costs versus outcomes by researchers has gained increasing attention.

These researchers have criticized the methodology of the physician supply projections made by the AAMC, on the grounds that those models assume that physician supply is currently appropriately matched to patient demand are currently equal.

“The fact is that the way that those models operate is they basically take today’s physician utilization levels, across different types of insurance and for different populations, and simply project them into the future,” said David Goodman, director of the Center for Health Policy Research at Dartmouth.

George Sheldon agreed with Goodman that it is wrong to assume that supply and demand are equal, but for a very different reason. In Sheldon’s view, there are already too few physicians in the country, not too many. In many specialties, including general surgery, there are already reports of shortages coming from many parts of the country, he argued (see sidebar). Thus, Sheldon said, projections of future shortages based on assumptions that the current supply is adequate wind up understating the extent of the future doctor shortage.

But Goodman maintained that increasing the supply of physicians into a dysfunctional healthcare system would only exacerbate that dysfunction.

“We know that new physicians don’t settle where needs are greater,” he said. “So you have this very irrational supply in the way that physicians are distributed.”

Goodman added that, according to Dartmouth’s research, there’s very little association between physician supply and patient outcomes, except when the physician-to-population ratio is even lower than it is projected to be in the next two decades.

In an email message, Goodman said that his research suggests that “the current training physician pipeline is likely to be adequate for another 10-15 years,” but he conceded that, as the population continues to grow, improving efficiency will not be enough, and the U.S. will need more health care professionals. Goodman added, however, that those professionals might be physicians, or they might be advanced practice nurses or physician assistants.

The signature argument of the Dartmouth group — that a greater concentration of physicians does not correspond to a greater quality of care — found eager listeners within the Obama Administration and among members of Congress during the debate over healthcare reform. (Dartmouth’s own methodology has recently been criticized.)

It has currency, in part, because of the group’s claim that the government can save a significant amount on healthcare costs by increasing efficiency in the current system. A crucial element of that increased efficiency, the group says, would be a greater focus on producing primary care physicians, who, as a group, are described as less likely to prescribe unnecessary tests and services while providing access to preventive care (something that, in turn, reduces the amount of expensive emergency care incurred).

Health and Human Services weighs in

Remapping Debate asked Edward Salsberg, the recently appointed director for the National Center for Workforce Analysis at the Bureau of Health Professions — which is housed within the Department of Health and Human Services — which side of the debate he came down on.

“There is no doubt that we are heading for a shortage,” Salsberg, who formerly worked at AAMC, said. “Those who challenge that fact suggest that if the world were different, then we wouldn’t need so many. I agree with that, and certainly this Administration is committed to improving efficiency and effectiveness, but the forces of the growing the population and the aging of the population indicate that demand for services is going to continue to rise.”

At the same time, he added, there are serious problems with physician distribution that the Administration is attempting to address.

“I don’t understand why it’s an either-or,” Salsberg said. “You have to do both. Clearly the strategy is to increase supply, and also try to improve the delivery system.”

Most advocates agree that raising the cap on residency positions funded by the government would be an effective way to increase supply while also improving efficiency, because new positions could be strategically created to address distribution issues, both geographically and among medical specialties.

When Remapping Debate asked Goodman whether he would support a proposal to lift the cap if it also included provisions oriented toward remedying problems with distribution — such as providing incentives to promote primary care residencies or targeting new residency positions to places where supply is currently low — he said, “I think that would be great public policy.” He added, however, that removing the cap without restrictions would exacerbate current imbalances in specialties and geographic location.

Past efforts foiled

Despite increasing pressure from the medical community, government action in the last few years has been limited. There have been some efforts on the part of lawmakers, like the proposed Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act, which was introduced in the Senate by Bill Nelson (D-FL) and in the House by Joseph Crowley (D-NY) in 2009.

The bill would have increased the number of Medicare-supported training positions by 15 percent, and included provisions that would have targeted the increase to primary care and given preference to hospitals that emphasize training in community health centers.

Both bills died in committee, but were revived last year as a Senate amendment to the health care reform bill. Despite being co-sponsored by several high-ranking Democrats, including Harry Reid, Charles Schumer, and John Kerry, the amendment failed to become part of the final bill.

Christiane Mitchell of the AAMC said that she was disappointed that the amendment wasn’t included in the PPACA, and she attributed its failure to its cost, which was about $1.5 billion dollars a year.

“The money has always been a tremendous obstacle,” she said. “Congress couldn’t find an offset for the cost, and that is the biggest hurdle.”

No one denies that training doctors is expensive. Each new residency position can cost as much as $110,000 a year. Much of that amount goes to the hospital for training costs, and residents’ stipends usually range from about $35,000 to $50,000 a year.

The health care reform bill does include some provisions that address problems with physician availability, including five years’ worth of funding for the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education Program, which will train primary care residents in community health centers around the country. Salsberg acknowledged, though, that the funding authorized — about $230 million — was not substantial, and that the program was only funded for five years. The bill also contains a provision designed to redistribute existing residency slots more efficiently (reallocating those that have gone unfilled in the last three years), but does not add new residency slots.

The healthcare reform legislation also created the National Health Care Workforce Commission which is charged with analyzing both supply and distribution issues in the workforce and reporting its findings to Congress. The first of two mandated annual reports by the commission is likely to appear in the next few months.

Little action for now

While there are some rumblings of new attempts to fund more residency spots through Medicare — staffers in both the offices of Senator Bill Nelson and Representative Joseph Crowley, sponsors of previous residency expansion legislation, confirmed that new proposals were being drafted or assessed — no bill on residency funding has been introduced, and no assistance for the creation of new medical schools is even being discussed.

And moving a bill will be a tough sell. According to staff in the office of Ways and Means Committee member Jim McDermott (D-WA), for example, the Congressman has not seen conclusive evidence that justifies a significant increase in the total number of Medicare-funded residency slots.

In the Senate, even some Republicans who have acknowledged physician supply problems in the past may be hard to convince. Back in 2009, Senator Charles Grassley (R-IA), said, “[i]t is easy to see that increased health coverage is useless without a workforce to provide care.” In an email response to Remapping Debate last week, Jill Gerber, Grassley’s press secretary, reiterated that sentiment: “If the health reform law continues to be implemented as intended, demand for health care services will rise, which will create problems for access to care.” But Grassley is dissatisfied with the way residency slots are being reallocated (focusing on increases in states with physician-to-population ratios lower than that of Iowa), and, according to his spokesperson, does not believe that Congress should consider lifting the residency cap until allocation issues are resolved.

Even if a consensus were to develop in Congress around the need to train more physicians, the funding required would remain an obstacle, according to Michael M.E. Johns, the chancellor of Emory University and a longtime proponent of increasing the supply of physicians.

“It really comes down to the dollars,” he said. “It’s easy to turn a blind eye to something when it’s expensive.”

In December of last year, the report of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, titled “The Moment of Truth” (more commonly known as the Bowles-Simpson report), actually advocated for cutting Medicare funding to graduate medical education by $60 billion by 2020.

Salsberg added that he has not seen a willingness on the part of the country to “open up the floodgates again,” and fund measures that would increase the supply of physicians.

According to some advocates, that “willingness” is likely to come only after the consequences of inaction become more tangibly apparent. And by that point, the window for addressing the shortage for the next decade may already have closed.

Johns said that he does not expect substantial action on the issue until Medicare patients stop being able to get appointments with their doctors.

Richard Cooper goes a step further.

“You won’t see anything done about this until people are out in the streets,” he said. “And by that point it will be too late.”