Oct. 24, 2012 — In late September, the Wall Street Journal reported that two large corporations — Sears Holding Corp. and Darden Restaurants Inc. — will soon dramatically change the way that they provide health insurance to their employees.

Beginning next month, Sears and Darden — the latter of which owns several restaurant chains, including Olive Garden and Red Lobster — will cease to offer defined benefits in which the employer, as part of its compensation package, provides employees with a set of health insurance benefits and continues to offer those benefits even when the employer’s costs for insurance rises. Instead, they will implement a defined contribution model, in which the companies will offer employees a fixed annual sum — like a voucher — that they can use to buy insurance for themselves and their families.

Although proponents of the defined contribution model promote it as serving the interests of employees, the results of Remapping Debate’s inquiries make clear that the central motivation is to shift the risk of rising health insurance costs from employers to employees.

Though Sears and Darden are the only large companies that have announced such a change as of yet, many observers believe that if the new model catches on, it could have huge implications for the health insurance system in the United States, and represent an end to the multi-generational compact between management and labor.

Looking out for the interests of their workers?

In order to justify the change to employees and to the public, promoters of defined contribution plans have launched a large-scale marketing campaign, the central claim of which is that a defined contribution model will benefit workers by giving them more “choice” of insurance plans and “empowering” them to make their own health care decisions. Both Sears and Darden claim that offering their employees greater choice is the primary reason for changing their model.

According to numerous health care experts, economists, and even some in the consulting industry itself, however, that rhetoric belies the true motivation behind the shift: reducing the company’s exposure to ever-rising health insurance costs by shifting those costs directly onto employees, who will be forced to either pay more out of pocket for the same level of insurance or pay the same amount for less robust coverage.

“Employers have been trying to cope with rising premiums for years by shifting costs onto their employees,” said Kathleen Stoll, the director of health policy at Families USA, a patient and consumer advocacy group. “This is really just one more strategy for doing that.”

Expanding choice or cutting costs?

The employees of Sears and Darden will not be using their defined contributions to “shop” for insurance in the broad individual market. Both companies will be participating in a so-called “private exchange” run by the benefits consulting giant Aon Hewitt, in which multiple insurance companies will offer multiple group plans, and employees will choose among the “menus” of plans offered. At the inception of the voucher system, employees won’t have to pay more than they do now to continue their current level of benefits (though they would have to pay more out-of-pocket for the premiums associated with the relatively high-benefit options).

Thereafter, the costs of a selected plan to an employee may rise faster than any increase in the size of the voucher the employer provides, and the elements of what a plan “buys” for an employee may be reduced.

These “private exchanges” — which share some similarities to the public state exchanges prescribed by the Affordable Care Act and are being marketed using some of the same rhetoric — are an essential part of the marketing strategy, according to patient advocates.

“These exchanges will let the employer create this menu of plans, which will allow them to say to their employees, ‘Look at all the choices we’re giving you,’” said Carmen Balber, the director of the Washington, D.C. office of the advocacy group Consumer Watchdog.

Indeed, Sears and Darden have been using that same rhetoric. Though Sears did not respond to requests to comment further for this article, a spokesperson told the Wall Street Journal that the shift “is about increasing associate choice and options for health care.” Ron DeFeo, a spokesperson for Darden Restaurants, told Remapping Debate that the company was responding to a perceived desire on the part of its employees for “more choice and more options.”

Aon Hewitt has released some promotional material about the exchange, and one of their white-papers reads: “The control over the coverage/contribution decision transfers from the employer to the employee, and with increased control comes increased satisfaction.”

According to several healthcare experts and industry insiders, however, neither company would be making this shift if they did not expect it to save them money. According to a recent survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Health Research and Education Trust, annual health insurance premiums have nearly doubled over the last decade, and most of that increase has been borne by employers.

“Cutting costs is far and away the number one reason for doing this,” said Greg Scandlen, a senior fellow at the National Center for Policy Analysis, a conservative think tank. “All other considerations are secondary.”

Michael Gusmano, an associate professor of health policy and management at New York Medical College and a research scholar at the Hastings Center, a bioethics and public policy think tank, agreed, calling the claim that employers are making this shift solely because they want to offer their employees more choice “nonsense.”

“Employers face large and growing costs for health insurance and are under pressure to reduce those costs,” Gusmano said. “In that context, it seems obvious that cutting costs is the primary motivation.”

Even the advertising materials issued to promote the exchange reveal that cutting costs — not providing more options to employees — is the main incentive for employers to make the switch to a defined contribution model (see sidebar titled “Decoding the pitch”).

Shifting costs onto workers

According to Gusmano and several other experts, there is only one way that a move to a defined contribution will save employers money, and that is by shifting more of the costs of health insurance onto employees. “This is going to do nothing to slow the rise in healthcare costs,” Gusmano said, “so the only logical reason for employers to do this is so that employees will have to pay more of those costs.” (See bottom box titled “Will competition drive down costs?”)

The most likely way for that to happen is that the employer’s contribution will either be frozen at the current level or will rise at a rate that is slower than the annual increase in health insurance premiums. That rate has averaged about 7 percent over the last 10 years for family coverage, and most economists expect it to increase by at least five percent a year in the foreseeable future, despite the reforms and cost-control measures implemented as part of the Affordable Care Act.

If the companies do not increase their contribution by at least as much as the rise in insurance costs, the employer’s contribution will pay for less and less of the costs of insurance premiums, which will mean that, to buy the same level of coverage, workers will have to pay an increasing amount out of their own pockets.

“The first year out, they might hold employees basically harmless from the prior year, so they can tell employees that they won’t pay any more out of pocket than they did last year,” said Kathleen Stoll of Families USA. “But over time it’s a sure bet that the size of the defined contribution won’t grow as fast as premiums.”

Mark Dudzic, a longtime union leader and the national coordinator of the Labor Campaign for Single Payer, agreed. Even if companies do increase their contribution at the overall rate of inflation, he said, workers will lose.

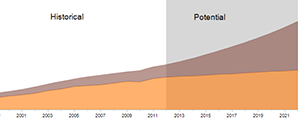

“Let’s say they’re currently paying $10,000 per employee for health care coverage,” he said. “If the CPI” — the Consumer Price Index, or the most common measure of overall inflation — “goes up two percent a year, and healthcare costs go up five percent a year, then next year [the company is] going to give $10,200 and the plan will cost $10,500. And the year after that, and the year after that…so you’re going to see those growing spreads.” Using the same calculation and assuming the same numbers, after ten years the gap between the contribution and the cost of insurance would be more than $4,000 (see sidebar titled “A growing gap”).

But because the increase in costs borne by the employee will be gradual, the employees might not become immediately aware of it, said Balber of Consumer Watchdog.

“Decreasing the contribution over time is much less visible than simply dropping coverage, so people may not immediately be as worried,” she said.

Alternatively, if the cost of coverage is rising faster than the employer’s contribution, the employee may feel forced to sign up for an insurance policy that costs the same amount but which offers less robust coverage.

“If the employer has a fixed amount of money to work with that is not increasing as fast as the cost of insurance, then we would expect that to lead to an erosion in coverage over time,” said Leonard Fleck, a professor of philosophy and medical ethics at Michigan State University.

For example, Fleck said, employees might opt for a plan with a lower premium and a higher deductible, meaning that they will pay more out-of-pocket for any care they receive. “So then if you get sick or you fall down the stairs and break your hip, you could quickly rack up a lot of medical bills,” he said.

While the Affordable Care Act does provide some protections in terms of what benefits an employer must offer and how much an employee can be forced to pay, many of those regulations have not been fully written, and patient advocates see risks that many of those provisions may not adequately protect workers (click here for our detailed explanation).

Several experts pointed out that benefits have already been significantly eroded in the group insurance market, as many employers have switched to “consumer-directed” health care models in which low premiums are coupled with very high deductibles and occasionally a health savings account. But Stoll of Families USA said that the implementation of the fixed contribution model could greatly exacerbate that problem. When their contribution to health insurance is already limited to a fixed amount, Stoll said, employers will be more liable to make changes to that contribution. If the company has a bad year, for example, it may simply choose to freeze the contribution or even lower it in order to cut costs.

“It has the potential to become a dial that’s very easy to turn,” Stoll said.

Additionally, there is no guarantee that, over time, the plans available to workers in the exchange will not themselves erode. If larger and larger numbers of workers are pushed into lower-quality plans because the higher quality plans are not affordable, Fleck explained, then higher quality plans may be eliminated for lack of demand. If that happens, then what is currently considered a “bronze” level of coverage might eventually be re-labeled as a “gold” level of coverage.

“Really high-quality coverage could become out of reach” for the ordinary worker, Fleck said.

When asked whether Darden was providing any guarantee to workers that the coverage available to them through the exchange would not erode over time, Ron DeFeo, a spokesperson for the company, said only, “We’re taking this one year at a time.”

A profound lack of control

Uwe Reinhardt, a professor of economics and public affairs at Princeton University, scoffs at employer claims that workers were being given “control.” He said that the marketing rhetoric claiming that employees will gain choice and empowerment is “disingenuous.”

“Corporations can spend billions of dollars on marketing and benefit consultants, so of course they wouldn’t say that this is an age of austerity and we’re going to ram this down your throat,” he said. “You find some mellow way to say it, in this case ‘choice.’”

Gusmano of New York Medical College found the advertising ironic. “When they say ‘choice’ what they mean is that, yes, you have greater flexibility and more plan options, but fewer and fewer of them are going to be affordable to you,” he said. “What they’re really doing is restricting choice.”

Indeed, even Aon Hewitt’s own promotional documents reveal that providing choice is not the primary motivation behind switching to a defined contribution model.

“Subsidies may be set to increase at a compensation rate of trend (2% or 3%) versus a traditional health care rate trend (7% or 10%),” says Aon Hewitt’s brief on “corporate exchanges.”

Nevertheless, DeFeo, the spokesperson for Darden, insisted that the company was planning to increase its contribution at the same rate at which health insurance premiums rise. That would mean the company was not planning to leverage the principle advantage that Aon Hewitt, the exhange manager it has selected, says a defined contribution model offers: “jumping off the health care trend curve [to] create significant cost savings and increased shareholder value.” Sears has not promised to increase its contribution as the same rate as the rise in health insurance premiums.

Other examples

Aon Hewitt’s exchange is not the only one currently in operation, and other benefit firms — including Towers Watson, Aon Hewitt’s main competitor — are preparing to enter the market in the coming months. Some smaller exchanges already exist, such as one run by Bloom Health Corp., which caters to smaller employers and was recently purchased by the insurance giants Wellpoint, BlueCross BlueShield of Michigan, and the Health Care Services Corporation.

In its promotional materials, Bloom Health profiles one of its clients — the Orion Corporation of Minnesota — which switched to a defined contribution strategy in May, 2010. According to the white-paper, Orion did not increase its contribution from 2011 to 2012, “in order to control spend[ing], and Bloom Health’s structure will allow employees to make individual adjustments or changes. Moving forward, Orion will evaluate when and where it needs to make changes to its contribution.”

Another exchange, run by a company called Liazon, has been catering to small businesses for five years. Liazon has labeled its exchange “Bright Choices,” but in an interview with Remapping Debate, the company’s co-founder and chief strategy officer, Alan Cohen, agreed that the primary motivation for companies to switch to a defined contribution model is to cut costs and said that many of the company’s clients have increased their contribution at a rate that is slower than the increase in the cost of health insurance over time.

“Their employees are finding plans that are less expensive,” he said, choosing, for example, plans with higher deductibles and lower monthly premiums.

Mike Thompson, a principal in the human resource practice at the benefits consulting giant PriceWaterhouseCoopers, said that the key part of the defined contribution model is that “employees are going to be willing to accept things that maybe they weren’t willing to accept before,” including “narrow networks and higher deductibles.”

When asked to explain how the shift could be billed as a good thing for employees, Thompson said, “Of course employees would prefer that nothing changes, but that’s not an option.”

“If the choice is this or dropping coverage altogether, I think this is the option they’ll prefer,” he said.

What’s next?

According to Jacob Hacker, a professor of political science at Yale University and an expert on the American health care system, if the defined contribution health insurance model were to catch on, it would fit into a larger, historical context.

“The fundamental thing to recognize is that this is part and parcel of the more general risk shift,” Hacker said. “The reality is that health care, retirement, all of the fundamental sources of security are shifting from larger organizations like employers and the government onto individuals.”

Hacker said that employers have been trying to find ways to shift the cost of providing health insurance for a long time. Indeed, the defined contribution has even been tried before, though employee backlash made it infeasible (see sidebar titled “Déjà vu?”).

If Sears and Darden succeed where others have failed, it could spark a trend that carries over to other companies. “Any time there’s a move like this among market leaders, the potential for a sea change is there,” said Thompson of PriceWaterhouseCoopers.

According to Reinhardt, if that happens, and large numbers of workers are faced with ever-growing health care costs, it could “naturally unravel” the system of health insurance benefits that American workers have been used to for decades.