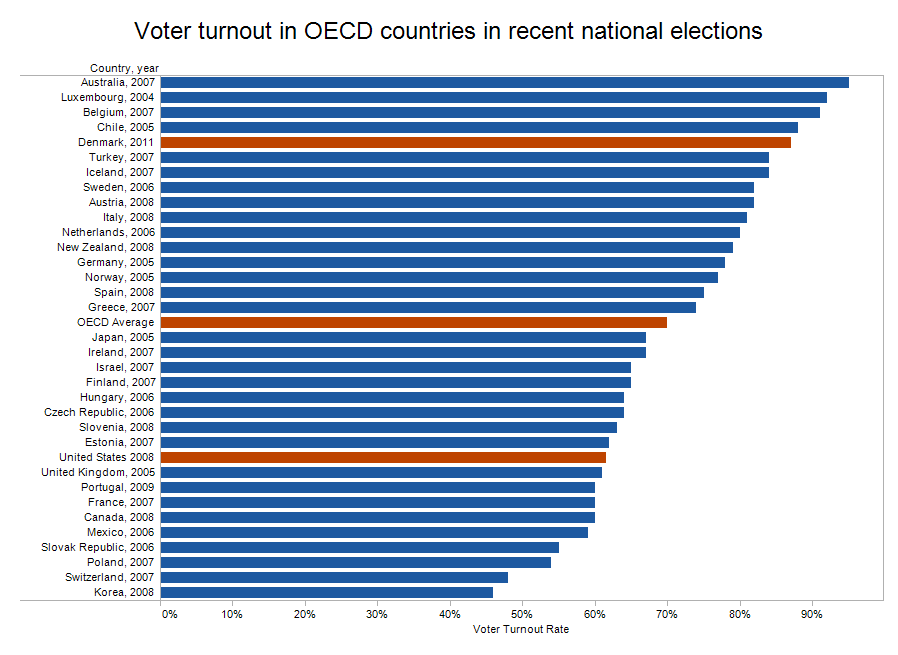

Sept. 21, 2011 — In last week’s parliamentary election, an estimated 87 percent of Danes went to the polls to vote. That figure represents one of the highest voter participation rates in the world, especially when countries with compulsory voting are excluded from the rankings. But for Denmark, this is nothing new.

“We have always had a very high degree of participation,” said Ove Korsgaard, a Danish historian at Aarhus University. “Unlike in most countries, we haven’t had big declines in the last 20 or 30 years.”

According to many Danes, much of the explanation for Denmark’s high level of public engagement can be found in the country’s institutions, which have evolved over the last several decades both to reflect and reinforce the notion of collective responsibility. “There are many ways in which Danish society reinforces a [shared] sense of citizenship,” Korsgaard said, stressing the interplay of multiple factors. From the welfare state to the public education system and from the tax system to the media, it appears that an emphasis is placed on putting the public good before the private good.

Co-citizenship

Korsgaard said that the participatory nature of Danish democracy is rooted in Danish history and stems from a strong national identity and collective spirit. “It’s quite remarkable that we have maintained this when you look at what has happened in the rest of Europe and in North America after the Second World War,” he said. “In Denmark, the nation is still thought of as a collectivist project. There is a much stronger sense of coherency and citizenship than in most other countries.”

There are two different words for citizenship in the Danish language —statsborgerskab and medborgerskab. The former translates to state-citizenship and refers to the legal conception of citizenship. “Statsborgerskab means you have the right to vote and you have a Danish passport,” said Jørgen Goul Andersen, a political scientist at Aalborg University.

By contrast, medborgerskab translates roughly as co-citizenship and is used to denote a broader conception of an individual’s role in society. “It is the notion that citizenship means having rights but also being willing and able to participate in society,” Goul Andersen said. “It is used to talk about civic-ness and the duties that each member of society has to the rest of society.”

That mutual relationship between state and citizen — the give and the take — is a central part of the Danish notion of collectiveness, Korsgaard said, and it is evident in many aspects of Danish life and policy.

For example, Goul Andersen said, Danes are very likely to participate in matters concerning their local communities. “The majority of Danish parents are in some way involved in their children’s school.” he said. “If something is not working, especially in the public sector, it is very common for people to attempt to influence it somehow. There is a sense of responsibility to make sure that things are working smoothly.”

That sense of responsibility can extend to ethical matters, as well. Remapping Debate asked Per Jørgensen, a college student in Copenhagen, what he thought his responsibilities were as a citizen. He mentioned voting and knowing about politics, but he also said that it was important not to take advantage of the rest of the society, noting that even small infractions, such as jaywalking — known in Denmark as “burning the red” — are considered taboo.

“If you’re going to burn the red, be careful that there is nobody around with children, because they will be upset that you are setting a bad example,” he said.

The welfare state

In the aftermath of World War II, and of the hardships that Danes endured during the war, there emerged a widely shared sense of solidarity between and among Danes. According to Goul Andersen, that sense has been constantly cultivated and reinforced over the decades since. “We have set up a system of social institutions that work to support this idea of active citizenship,” he said.

Perhaps Denmark’s signature achievement is its extensive welfare state, which is one of the most generous in the world. “There is still a general consensus that to be a Dane, this idea of Danishness, means to be in favor of the welfare state,” Korsgaard said. In stark contrast to the United States, none of the political parties running in the recent election advocated for deep cuts to the state.

Britta Paulsen, a nurse in Copenhagen, said in an interview in July that she, along with almost all other Danes, had reaped the benefits of the welfare system through the free and universal services it provides — such as health care, education (including higher education), child care, eldercare, and parental leave — and that she was therefore willing to pay the high taxes that are necessary to finance it.

“In Denmark if a politician tries to lower taxes, we vote them out,” she said, “because we know that that means that we will have to cut something.”

But Paulsen added that the welfare state also reinforced the sense of civic duty from which it was born. “We have grown up with it,” she said. “I think you can ask anyone on the street and they will tell you that part of being Danish is taking care of other Danes.”

Lars Lyngse, international counsel at the United Federation of Danish Workers, agreed.

“In Denmark we have been able to maintain a national identity, a national unity,” he said. “A big reason why we have been able to do this is because we don’t have a lot of people falling through the cracks.”

Education

While the welfare state is perhaps the best known outgrowth of the Danish conception of citizenship, Korsgaard said that it cannot be viewed in isolation from a number of other features in society, which have an interrelated role in reinforcing the civic-mindedness.

The Danish education system, for example, places a high degree of emphasis on civic education. In fact, preparing students to take an active role in democracy is one of the public education system’s primary objectives, as defined in the folkeschool (public school) charter:

“[The education system must] prepare students for active participation, joint responsibility, rights and duties in a society of freedom and democracy. The teaching and the whole school’s daily life must therefore build on intellectual liberty, equality and democracy. Students will thereby acquire the preconditions for active participation in a democratic society…”

“The purpose of school is in the first place to provide qualifications for society and then to socialize kids to active citizenship,” Goul Andersen said.

Jens Ulrik Engelund, a schoolteacher in Copenhagen who teaches social science, history, and economics, said that the public school system attempts to instill in students, from an early age, a sense that they are part of a society and that they have certain responsibilities to it, as well.

“We always try to explain to students why we are making them learn something,” he said. “So when we are teaching about Danish history or government or policy, we tell them, ‘If you want to live in this society, and not just live in it but take part and have a say in the direction of society, then you must learn about your civic rights and duties.”

While schools offer no course in civics per se, Ulrik Engelund said that lessons about Danish democracy and policy are woven into several subjects, including history, economics, and social science. In high school, students are encouraged to actively debate issues in class. “Students come with all sorts of values and opinions, and we encourage them to debate them,” he said. “We have very heated discussion over what is best for the country.”

Remapping Debate spoke with Ulrik Engelund by phone the day after the Danish election. He said that, though they are too young to vote, many students had gone to the polling sites simply to see the process at work. The week before, various politicians running for Parliament visited a number of Copenhagen schools, including the one where Ulrik Engelund teaches, to meet students, make speeches, and hold debates.

According to Korsgaard, the Danish tradition of civic education is another way in which the Danish sense of citizenship has successfully propagated itself through time.

Ulrik Engelund agreed. “We are very proud of the education program,” he said. “As teachers, we feel that teaching the students about democracy is a way we are contributing to it, the same way that we were taught.”

Transparency and trust

Peter Abrahamson is a professor of sociology at the University of Copenhagen, who has long studied Danish institutions and policies and their impact on what it means to be a citizen. According to him, one of the central factors that has allowed the Danish democracy to function so well is that a very high level of trust exists among Danes — not only trust of the government, but also of social institutions like unions, private businesses, and of other Danes.

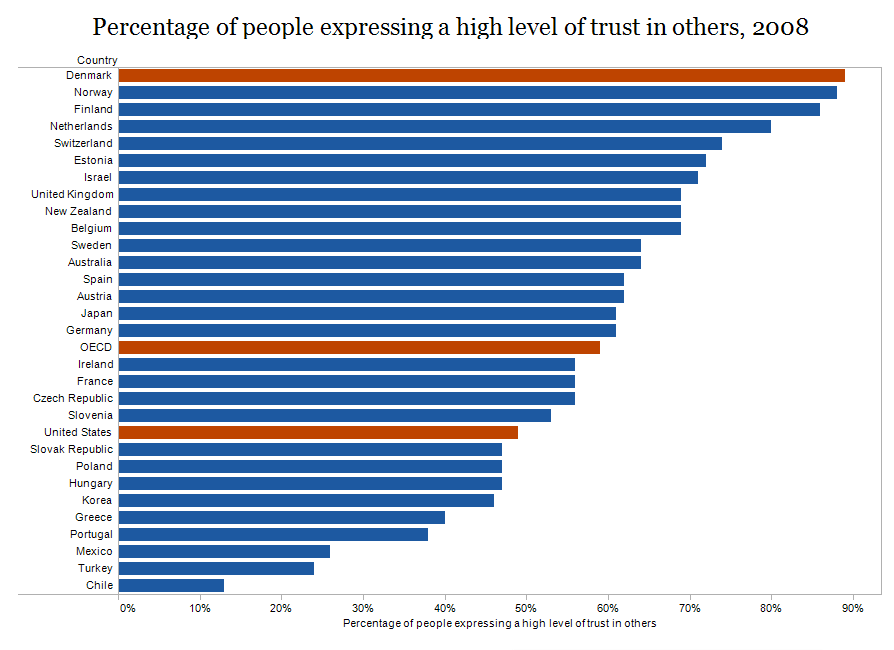

“Social trust” is measured by several international organizations. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) produces a survey every year in which it asks citizens of different countries the question, “Generally speaking would you say that most people can be trusted or that you’ll need to be very careful in dealing with people?” Last year, Denmark registered the highest percentage of people who responded that they had a high level of trust in others, at 88.8 percent. The average of OECD countries was 59 percent, and in the United States, only 48.7 percent of respondents expressed a high level of trust (see chart).

Transparency International conducts a similar annual survey among countries called the “Corruption Perception Index,” where respondents are asked how much trust they have in government. Denmark has been ranked highly on this survey as well, tying two other countries for first place in 2010. “When you have such high levels of trust, that leads to greater participation and a stronger feeling of collectiveness,” Abrahamson said.

According to Abrahamson, a major reason that Danes are so trusting is that they have set up institutions that facilitate that trust, leading a virtuous, self-reinforcing cycle similar to the one that links the welfare state and the civic education system.

“People would not be so willing to pay so much in taxes if they thought that others were somehow cheating the system,” he said. “So we set up institutions that are very transparent and very hard to cheat. When no one cheats, it becomes more socially unacceptable to cheat.” The Danish tax authority, for example, frequently audits employers, Abrahamson said, reducing the likelihood of tax evasion.

And because trustworthiness is such a strong social value, Danes expect their politicians and public institutions to maintain a high degree of honesty and transparency, as well. Goul Andersen noted that in the recent campaign, a Danish politician had cited some statistics about poverty and inequality that proved to be misleading. “He had used a different measure to calculate them than the one that is usually used,” he said. “There was a very strong public reaction to that, and it was in all of the big papers.”

In that way, social trust had become a mutually reinforcing aspect of Danish society, Goul Andersen said. “We have been able to maintain this very high level of trust because we have incorporated it into our institutions,” he said.

Another crucial factor in maintaining high levels of trust is that Danes are not very open to manipulation by the government, Goul Andersen said. “[Danes] are relatively knowledgeable about how things work and are supposed to work,” he said.

Equality

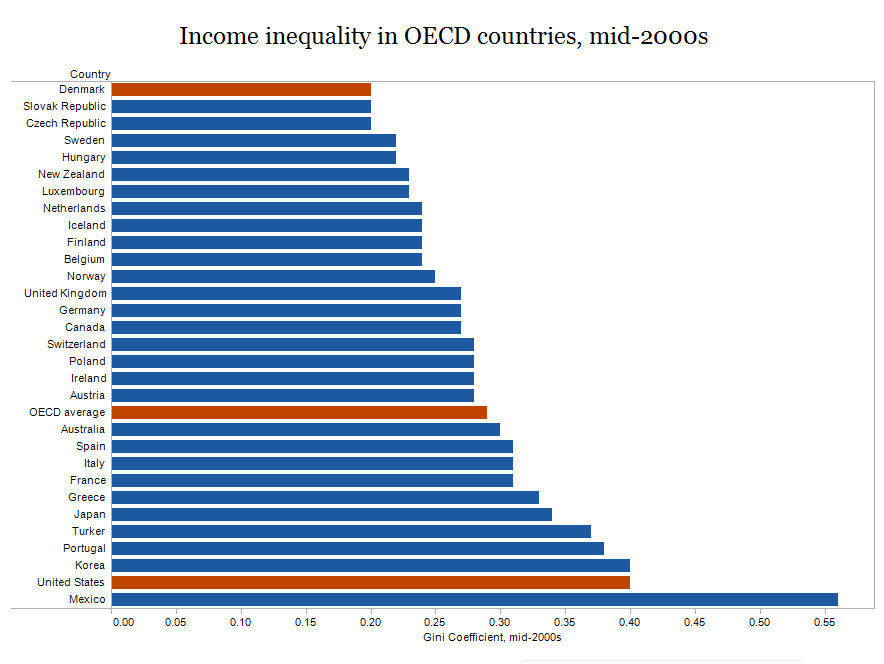

The Danish system of progressive taxation and redistribution has created one of the most equal societies in the world. Income inequality is typically quantified using a system called the “Gini Index,” a statistical tool that measures the proportion of total wealth that is owned by various percentiles of a country’s population; the lower a country scores on that index, which usually runs on a scale from zero to one, the more broadly shared its wealth. Denmark’s Gini “coefficient” was 0.20 in the mid-2000s, according to the OECD, placing it in a three-way tie for the most equal country in the OECD. The OECD average was 0.29, while the United States, at 0.40, was second to last behind Mexico among OECD countries (see chart).

And this equality has also become integrated into Danish institutions. Per Jørgensen, the college student, named equality as the primary Danish virtue. “Most Danes would say that it is harmful for society to be very unequal,” he said. “I think that is something that Danes have in common.”

Goul Andersen described how Denmark has been able to maintain a high degree of equality even as most countries have grown more unequal in the last generation. “It is, again, a virtuous cycle,” he said. “Social equality leads to political equality, which leads to political decisions that reinforce that equality.”

Because large degrees of inequality do not exist in Denmark, there is a far lesser degree of difference between the general electorate and the officials who represent them in government.

Niels Buhl, who owns a small store in Copenhagen, said that he had only missed voting in one election in his life, and that was while he studied abroad in Germany. “My parents always told me that it is important to vote,” he said. When asked whether he felt that there was a big divide between himself and the politicians he votes for, Buhl pointed to the street outside, a busy thoroughfare that runs toward the seat of the Danish Parliament. “Sometimes you see them bicycle by here in the morning,” he said.

Work as central to citizen identity

Being an active part of the labor market has increasingly become part of a citizen’s obligation to society, Abrahamson said. From the end of World War II to the mid-1970s, the Danish government pursued a policy of full employment, which meant that it was the responsibility of the state to guarantee that its citizens had jobs. But after a prolonged bout of unemployment in the 1970s, that responsibility was shifted from the state to the individual, Abrahamson said.

“We began to say that this idea of ‘active citizenship’ means that while it is the state’s responsibility to provide you with education and training, it’s your responsibility to be working and paying your taxes, no matter what your capabilities are, or what the economy looks like, or what kinds of jobs you’re offered,” he said.

Many Danes feel that this shift has contributed positively to the sense of collectivity. “If we want to enjoy this society, then we all need to be working,” said Jørgensen. “That’s only fair.”

According to most Danish economists, in order to keep the large Danish welfare state in a sound position, fiscally, it’s important that as many people as possible are in the labor market. To that end, Denmark has put in place the most elaborate system of re-employment training in the world, and though the state does not guarantee jobs to citizens, it will often subsidize employers to hire people who are unable to find work on their own.

But Abrahamson believes that this emphasis on work has negative ramifications as well, because it effectively excludes those with less ability to work. “We have placed very high level of demands on people, but there is a segment of society that is not able to fulfill those demands, and so they are effectively marginalized,” he said. “They are not able to fulfill their full potential as citizens.”

Those who remain out of the labor market for a long period of time, either because they have less training or education or because of a physical or mental disability, are not seen by their neighbors as being productive members of society, Abrahamson said, adding that while there is not the same stigma attached to being unemployed in Denmark as there is in the United States, those who are consistently on “the government dole” risk being isolated from the rest of the community.

“The good story is that we are taking care of these people, they are not going hungry,” Abrahamson said. “But they are not really participating in mainstream society and they’re excluded from social contact.”

That shift in social attitude has been mirrored in changes to the welfare system. In the last decade, the right to nine years of unemployment benefits has been reduced to two, and if someone who is unemployed does not accept a job before those two years are up, he or she is thereafter provided with a less generous form of social assistance.

Another example is the rising use of private health insurance to supplement the free public insurance. “You now have one fifth of the population using a private health plan,” Abrahamson said. “It is quickly becoming a two-tiered welfare state, with a high level of protection for those who can be very productive, who are capable of participating fully, and a lower level for those who are not.”

Abrahamson said that he would like to see the government renew its commitment to full employment. “There always needs to be a balance between [citizens’] rights and duties,” he said. “I think we have been erring too far on the side of the duties.”

“Things just work better that way”

While many individual aspects of Danish society can be seen as both reflecting and reinforcing a strong sense of citizenship, Goul Andersen noted that, in practice, the pieces are interconnected. “Because we have this welfare state, that makes it necessary to have a system of civic education,’ he said. “Both of those things depend on trust and equality. Our political system depends on a high degree of trust and consensus between people on fundamental issues. If you remove one piece, you’re in danger of losing that.”

Korsgaard agreed. “Of course, it is all working together,” he said. “You can’t say, this is the reason. It’s much more complicated than that.”

Nevertheless, many Danes do not struggle to answer why they place such a high premium on civic-mindedness. Remapping Debate asked Britta Paulsen, the Copenhagen nurse, why she thinks there is such a big difference between Denmark and the United States in that respect.

“We realized that we can do more as a group than as individuals,” she said. “Things just work better that way, so that is how society was built.”