The rise and fall of guaranteed income

Though the specifics of such proposals — both in method of administration and level of support — differed considerably depending on the authors, “Among policy folks, academics, and activists…for a period of time there was consensus across the political spectrum that [GAI] was a pretty good idea,” said Brian Steensland, associate professor of sociology at Indiana University and author of the book, “The Failed Welfare Revolution: America’s Struggle over Guaranteed Income Policy.”

Support from very different sources

During the 1940s, conservative economists Milton Friedman and George Stigler had laid out the principles for a “negative income tax” (NIT). Each proposed to trigger government subsidy of a household when that household’s income dipped below a specified floor (the subsidy would have been designed to raise the household’s income to that minimum level), but at the time, the proposals were largely ignored.

Some on the other side of the political spectrum came to see a need for the GAI as well. In 1964, Michael Harrington, the socialist author of 1962’s “The Other America,” and other thinkers on the left wrote a letter to the President, Congress, and the Secretary of Labor arguing that, as automation continued to shrink the size of the workforce, income and work needed to be decoupled.

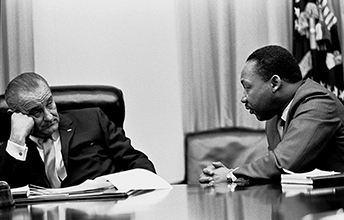

The “rediscovery” of poverty in U.S. — inspired in part by Harrington’s book and acted on by President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty — helped make the GAI a mainstream proposal by the end of the decade, as did critiques of the “welfare mess” emanating from activists and politicians across the political spectrum. (GAI was often synonymous with “welfare reform” during the Nixon years). Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), the program that had provided monetary subsistence mostly to single mothers with children was regarded as demeaning by many liberals due to its low benefit levels (which varied from state to state) and the fact that it reached no more than 30 percent of the poor. The same program alarmed conservatives because of its large bureaucracy, fears of creating a “dependent” welfare class, and concerns that the program’s structure encouraged the breakup of two-parent families (AFDC made it more difficult for a two-parent household to get aid).

A societal problem

If support for a GAI benefited from concerns across the political spectrum over what were seen as undesirable effects of existing programs, “The energy certainly was on the left,” according to Marisa Chappell, an associate professor of history at Oregon State University and author of the book, “The War on Welfare: Family, Poverty, and Politics in Modern America.” It was, Chappell said, “a moment when we actually see massive social movements demanding [changes].”

Public opinion

The scope of the public support for guaranteed annual income is not clear.

A 1965 Gallup poll — conducted before the concept had widespread visibility — showed only 19 percent of respondents favoring the proposition that “instead of relief and welfare payments, the government should guarantee every family a minimum annual income.”

The month after President Nixon announced the Family Assistance Plan in September 1969, however, 51 percent of respondents to a Harris poll for Life Magazine favored the proposal for a “federally guaranteed minimum level of income, with a bottom of $3,000 [2013: $18,978] a year for a family of four.”

That same month, Harris also asked specifically about the Nixon Family Assistance Plan (with the $1,600/year floor for a family of four): 79 percent of respondents favored it.

For example, in a 1967 book, Martin Luther King, Jr., a central leader in the civil rights movement, wrote that “we are wasting and degrading human life by clinging to archaic thinking” in failing to implement a guaranteed income. “A host of widespread positive psychological changes inevitably will result from widespread economic security,” King concluded. “The dignity of the individual will flourish when…he has the assurance that his income is stable and certain, and when he knows that he has the means to seek self-improvement.”

Implicit in the arguments for the GAI during the late 1960s and early 1970s was the sense that poverty was a problem that was the responsibilty of the broader society to solve. Senator Fred Harris (D-Okla.), for example, sponsored one “national basic income” bill, arguing as he introduced it in February 1970 that passage of a GAI would result in a “great moral dividend” for the nation. “It would allow us to feel,” Harris continued, “we are living more closely in line with the ideals we profess. We will more nearly be entitled to say that we believe in the dignity and value and worth of every human life.”

Harris’s sense that governmental solutions to social problems were both necessary and possible was not a minority position. Michael Katz, professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania and scholar of poverty and welfare in U.S. history, told Remapping Debate, “This was the era…when there were many new programs; where innovations in social policy that had seemed impossible had burst onto the scene and become plausible.” Citing the passage of Medicare and Medicaid (1965), the expansion of the food stamp program (1964), and the Fair Housing Act (1968), Katz characterized this historical moment as one where “the discussion of possibilities in social policy was much broader than it is today.”

The “possibilities” in social policy at the time indeed allowed ending poverty for all Americans seem, to Fred Harris, “not utopian.” The U.S. had already “made a strong beginning,” and Harris, the chairman of the Democratic National Committee from 1969 to 1970, said that the problem was only that “we have not carried our beginnings through their logical development.”

James Tobin, a former member of President Johnson’s Council of Economic Advisors who at the time was also a Yale professor, echoed this spirit in an article in The New Republic in 1967. Titled, “It Can Be Done! Conquering Poverty in the US by 1976,” Tobin argued for a GAI and believed that “if we seize the opportunity for a far-reaching reform, even at considerable budgetary cost, we can win the war on poverty by 1976.”