The rise and fall of guaranteed income

Guaranteed Annual Income legislation

In August 1969, in the eighth month of his presidency, Richard Nixon delivered a speech proposing the replacement of AFDC with a program that would benefit “the working poor, as well as the nonworking; to families with dependent children headed by a father, as well as those headed by a mother.” In case the point was missed, he continued: “What I am proposing is that the Federal Government build a foundation under the income of every American family with dependent children that cannot care for itself — and wherever in America that family may live.”

Guaranteed annual income had arrived. From the margins of economic thought just a generation earlier, the GAI was now at the heart of President Nixon’s domestic policy agenda in the form of the “Family Assistance Plan” (FAP).

Nixon himself refused to call the FAP a guaranteed annual income, saying that “a guaranteed income establishes a right [income] without any responsibilities [work] …There is no reason why one person should be taxed so another can choose to live idly.” But, despite Nixon’s rhetorical distinction, many conservatives opposed the president’s plan for just those reasons: they worried not only about cost, but also about the creation of a large class of people dependent on “welfare.”

Rhetoric aside, the FAP was indeed a form of GAI. The President’s Commission certainly thought so, writing in their letter submitting “Poverty Amid Plenty” to Nixon, “We are pleased to note that the basic structure of the Family Assistance Program is similar to that of the program we have proposed…Both programs represent a marked departure from past principles and assumptions that have proven to be incorrect.”

Nixon’s FAP was very moderate: it only applied to families with children (childless couples and individuals were out of luck), included a work requirement for householders considered “employable,” and would not have increased benefits for AFDC recipients in states providing relatively high benefit levels.

For a family of four without any other income, the FAP would provide $1,600 (2013: $10,121). But a family that did have income from employment would get a declining amount of FAP dollars until family income reached $3,920 (2013: $24,798). A family of four that had been earning $12,652 in 2013 dollars would have had its income increased through the FAP to $18,725. Ultimately, the vast majority of benefits would have gone to the “working poor,” a significant departure from then-existing programs that denied welfare benefits to those who were employed.

The FAP sailed through the U.S. House of Representatives comfortably, 243 to 155, but stalled in the Senate.

Many Congressional Democrats insisted that assuring the dignity of the poor required a more expansive program than the FAP, and criticized that proposal for its low income floor and work requirements. Representative William F. Ryan (D-N.Y.), who had been the first to introduce legislation for a GAI (in 1968), told the House in April 1970 that “accepting the concept of income maintenance and establishing the mechanics for implementing that concept are two far different things.” And though Ryan suggested “we do well to embrace the concept,” he characterized Nixon’s FAP as “seriously flawed.”

As an alternative, Ryan pointed to the proposal of the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO), which had argued for a much higher base income: $5,500/year (2013: $32,910). Ryan argued on the floor of the House of Representatives that:

[A] guaranteed annual income is not a privilege. It should be a right to which every American is entitled. No country as affluent as ours can allow any citizen or his family not to have an adequate diet, not to have adequate housing, not to have adequate health services and not to have adequate educational opportunity — in short, not to be able to have a life with dignity.

Come Home, America

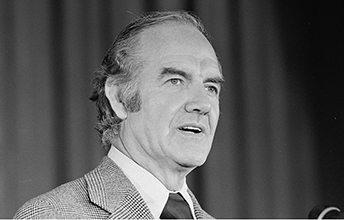

Nixon and Congressional Democrats, though, were not the only ones with a plan. In fact, the 1972 Democratic nominee for president — Senator George McGovern (D-S.D.) — rolled out his own GAI proposal in January of that year. McGovern suggested that “every man, woman, and child receive from the federal government an annual payment,” a payment which would “not vary in accordance with the wealth of the recipient” nor be contingent on the family unit. In contrast to Nixon, McGovern believed payments should be made to individuals and childless couples.

Drawing on his economic team, McGovern discussed a few specific proposals, including a James Tobin-inspired plan with a $1,000 per person minimum income ($5,554 per year in 2013 dollars), but emphasized that further study on configuring the plan would be necessary and “pledge[d]” that “if elected,” he “would prepare a detailed plan and submit it to the Congress.”

McGovern did begin to encounter criticism from some Democrats who suggested that he would be excoriated by Nixon for a proposal that, by some estimates, would subsidize 67 million Americans (almost 32 percent of the population). In the summer of 1972, McGovern shifted the focus of his policy proposals away from GAI and towards a full-employment agenda.

In August, McGovern presented what he called “national income insurance” to the public, a plan that would have provided “jobs for those who are able to work [through public service employment], a reasonable income for those who cannot work [$4,000 per year for a family of four, or $22,275 in 2013 dollars], and truly adequate Social Security” for the elderly and disabled.

Not entirely confortable with this formulation, McGovern added, “we must resolve the question of income supplements for working people who, in spite of their labor, still have trouble making ends meet. Even the unacceptable Nixon Family Assistance Plan recognizes the need to boost the income of those who earn too little.”

The candidate remained committed throughout the campaign both to the view that “our country lacks neither the means not the will to meet the human needs of all of its citizens,” and to action that would have been at least the functional equivalent of a modest GAI.