Jump to

April 15, 2025 — Former Governor and current mayoral hopeful Andrew Cuomo’s recently released housing plan (link in sidebar) has thus far garnered most attention for rejecting for now, with limited exceptions, any upzonings for low-density neighborhoods to facilitate the affordable-housing development those neighborhoods have resisted for decades, and for the plan’s apparent use of ChatGPT (according to a Cuomo policy advisor, for research only). But the plan is at least as notable for Cuomo’s interest in re-litigating a fair housing lawsuit that New York City resolved with a consent decree1 entered in January 2024. [Skip immediately to the annotated version of the Cuomo position statement.]

This article is a matter of first-hand reporting: I was and remain lead counsel for the plaintiffs in the case. The case, brought in 2015, had challenged the City’s longstanding outsider-restriction policy in affordable-housing lotteries. Rather than allowing all applicants an equal opportunity, the policy gave preference to those applicants who already lived in the community district in which the development was being constructed. Because New York City is so residentially segregated, that meant that the policy of giving “insiders” preference over “outsiders” inevitably resulted in the perpetuation of segregation.

The consent decree reduced the insider preference from 50 percent to a maximum of 20 percent as of April 2024, and ordered a further reduction to 15 percent five years thereafter. Among other provisions, Housing Connect (the City’s affordable-housing lottery portal) and all lottery advertisements were required for three years to display prominently an inclusive vision of the City completely at odds with the traditional view of New York as a series of turf zones, each owned by a particular racial or ethnic group:

New York City is committed to the principle of inclusivity in all of its neighborhoods, including supporting New Yorkers to reside in neighborhoods of their choice, regardless of their neighborhood of origin and regardless of the neighborhood into which they want to move.

The City’s Department of Housing Preservation & Development and its sister agency, the New York City Housing Development Corporation, have been reliably abiding by the decree, and the City, developers, community organizers, and other interested parties have moved on to other business.

Cuomo wants a do-over

In the position paper (as discussed in more detail in the annotated version that follows), Cuomo rehashes a series of arguments made during the litigation: that there won’t be support for affordable-housing development without going back to a 50 percent preference; that insiders in Black and Hispanic neighborhoods are uniquely vulnerable to displacement; that the preference prevents displacement; and, implicitly, that virtually everyone wants to stay in his or her neighborhood.

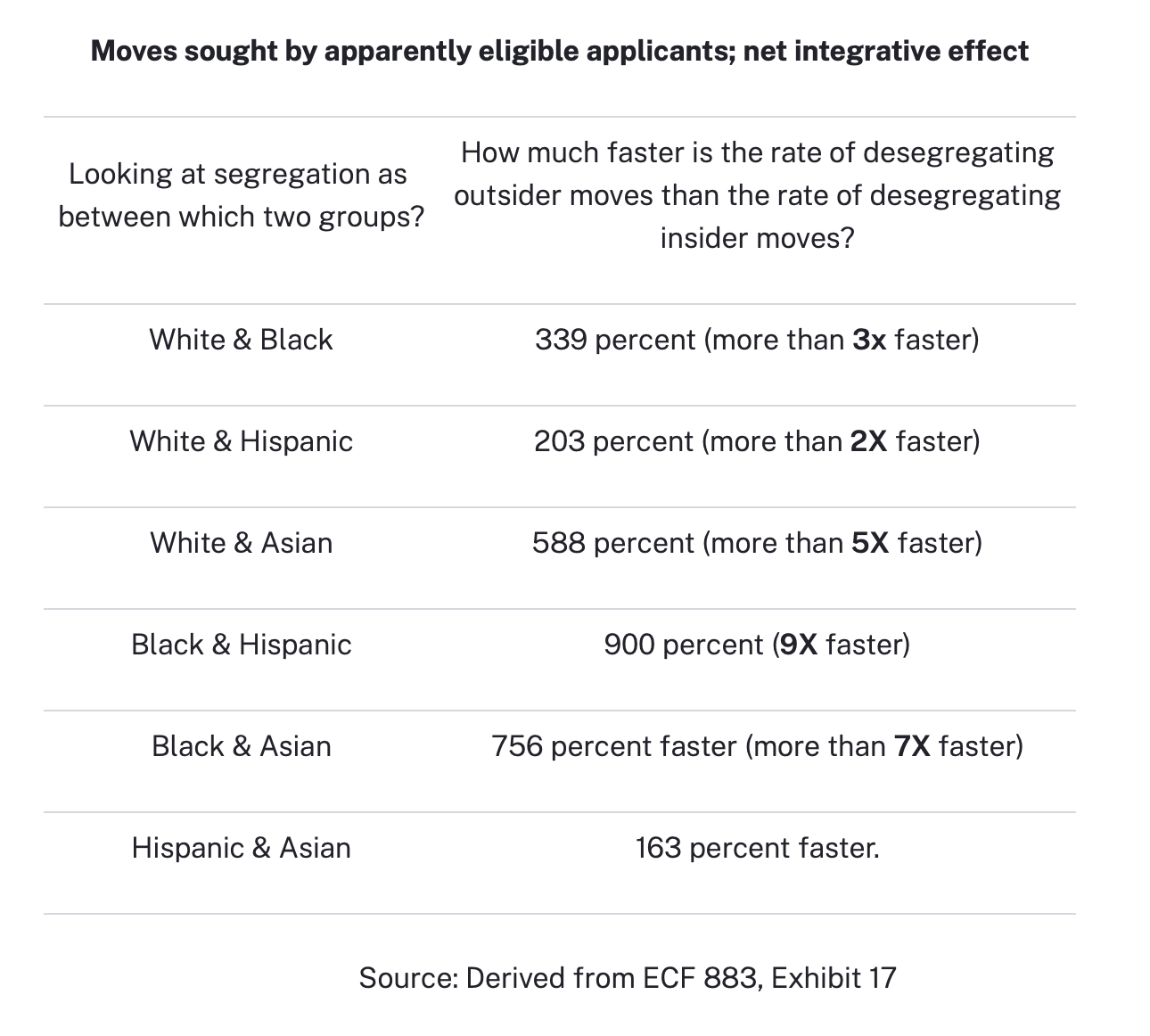

Cuomo downplays how powerfully the full, 50-percent version of the outsider-restriction policy slowed down the integrative moves that New Yorkers want to make.

Critically, Cuomo reprises a retrograde vision of New York City as a city that naturally, appropriately, and irremediably has racially and ethnically defined neighborhoods. It is impossible to read the position statement without understanding that Cuomo’s intended message here is that the “good” kind of segregation is reflected in neighborhoods that are disproportionately Black or Hispanic; there is no apparent understanding that those neighborhoods were created intentionally in the period when “White supremacy” was not a matter of contested rhetoric, but rather a brutal, every day reality.

In other words, the goal of the lawsuit — substantially but not entirely achieved — was to support the idea of honoring the choices that actual New Yorkers seek to make instead of honoring the choices that their officials think they should make. Cuomo wants to turn back the clock.

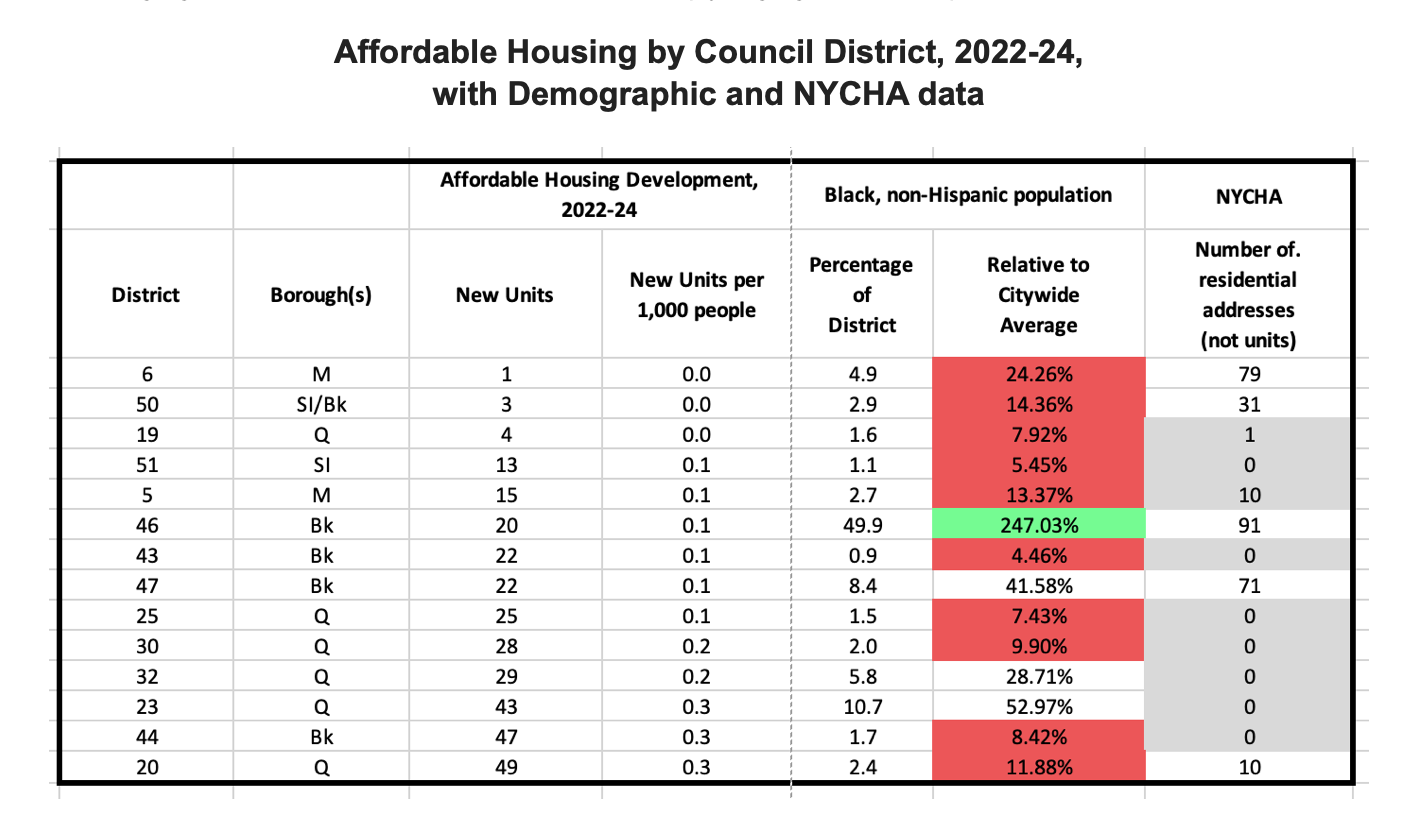

Last, Cuomo postures himself as bemoaning the fact that too little affordable housing is built in the City’s “high opportunity” (read: White) neighborhoods, and presents this as a problem that the consent decree did not solve. That is true, but the odd things are that Cuomo: (1) does not seem to realize that the person with the most power to change that dynamic is the Mayor of the City of New York; and (2) has, in this same position paper, given a thumbs-down to more affordable housing in low-density neighborhoods that mostly have disproportionately low percentages of Black residents (see sidebar on the community districts where the least affordable housing is being built).

What do the data say?

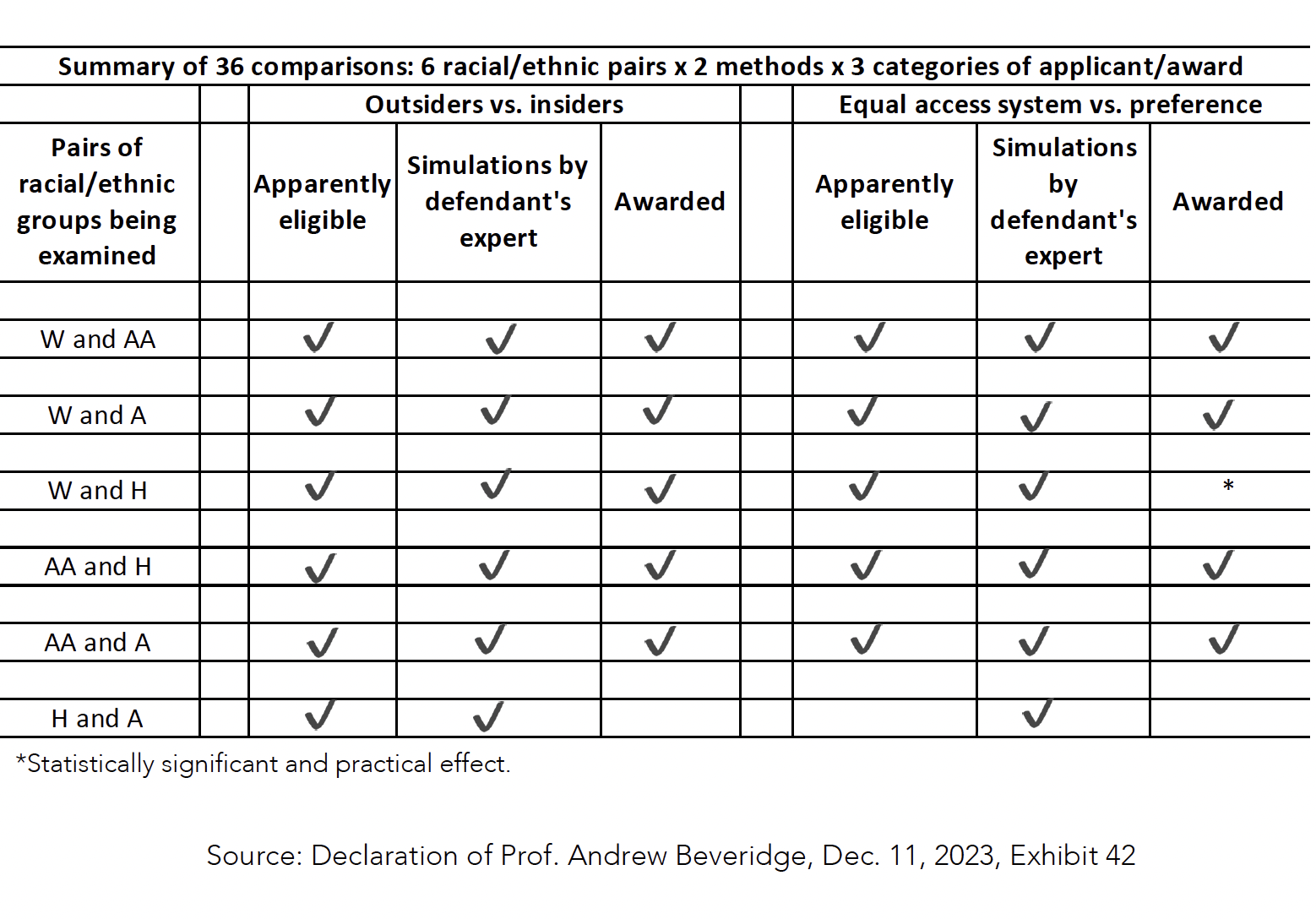

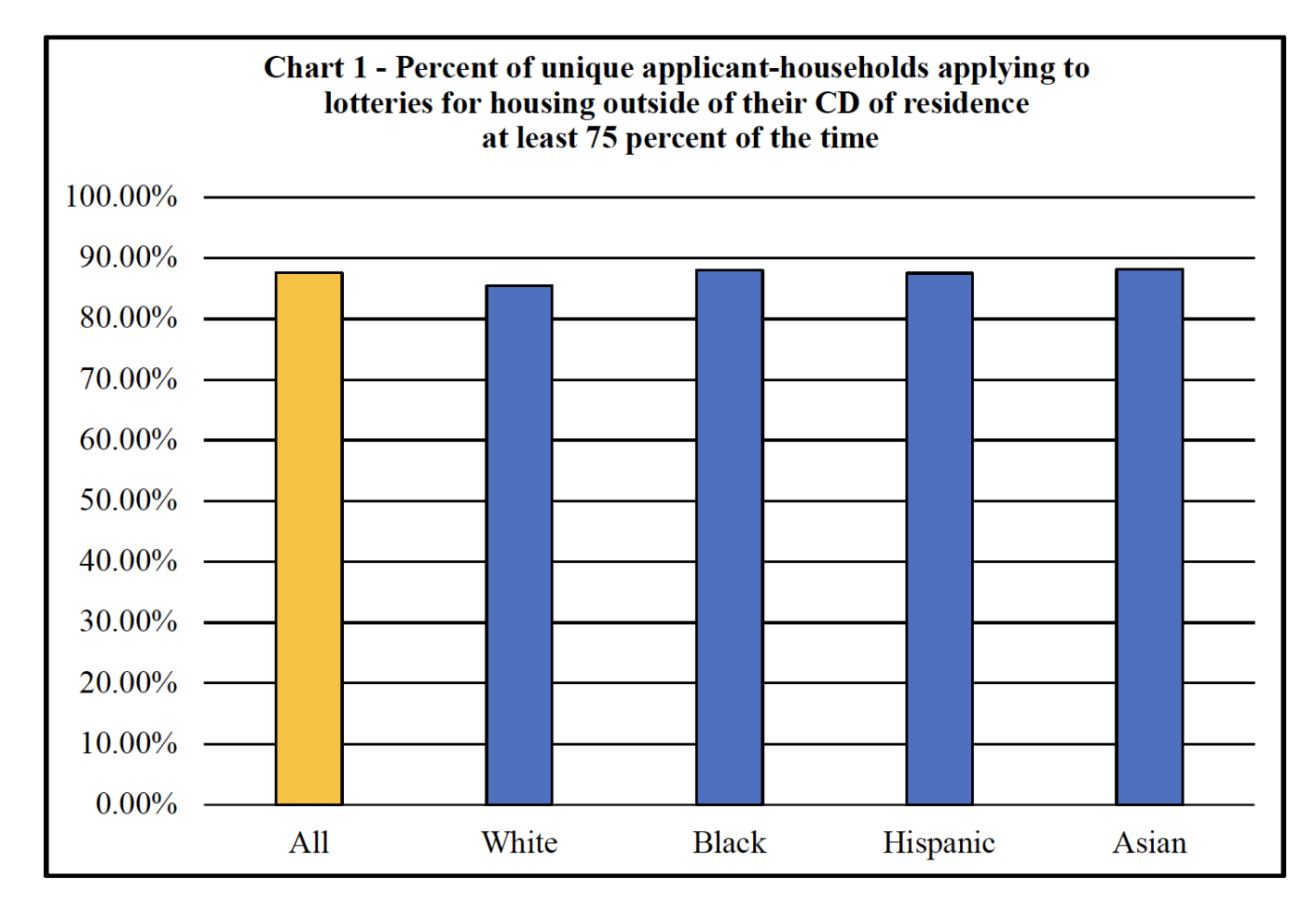

In fact, based on the several million lottery applications that were analyzed during the case, it became clear that the preference policy was stymieing significantly the integrative moves that outsiders to the community district disproportionately sought to make (see sidebar). And it also became clear that the segregation-perpetuating effect of the policy ranged across two-group comparisons and were material across multiple analytical methods (see sidebar).

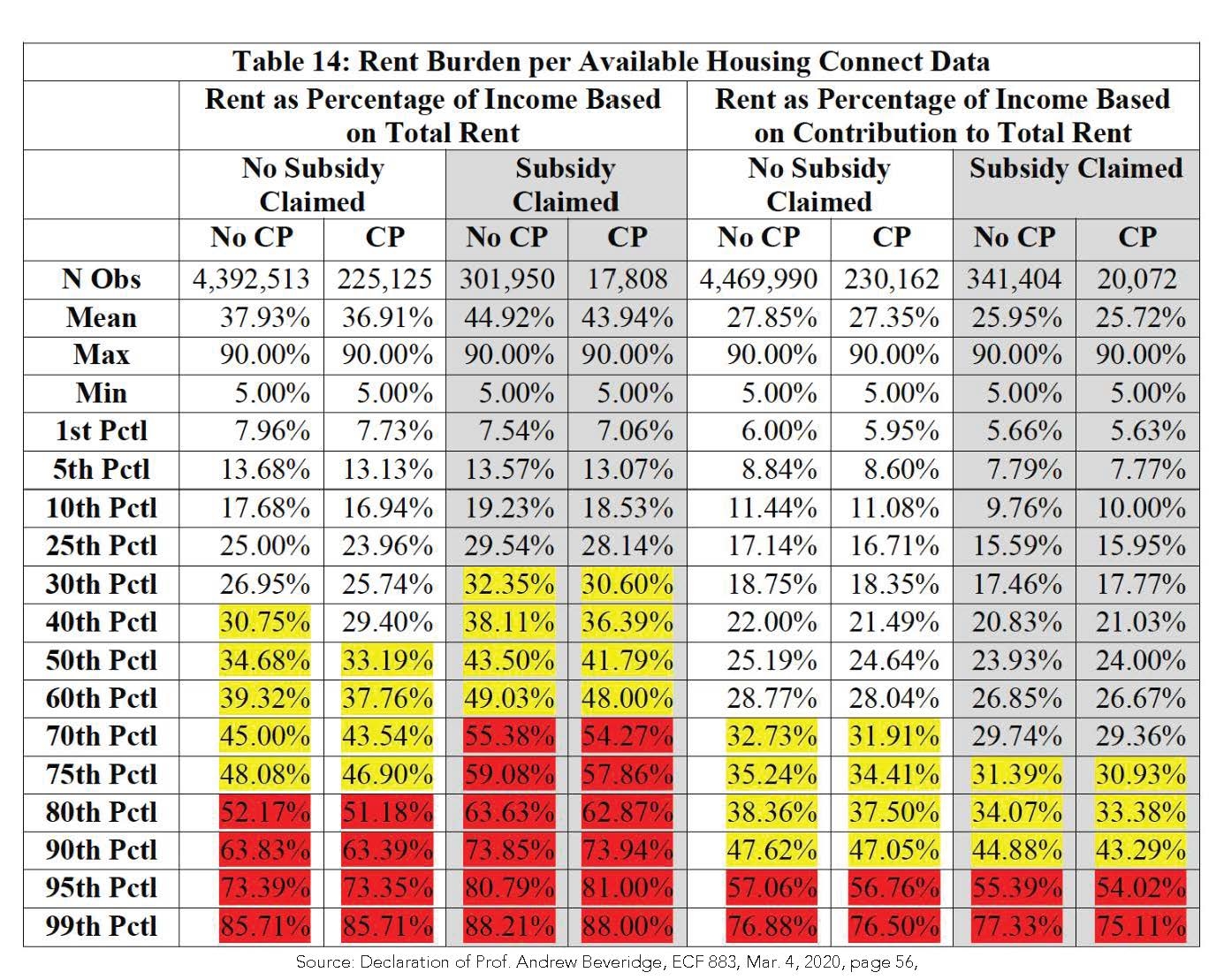

Cuomo ignored the fact that an eligible applicant for any particular apartment had to have the same household income, regardless of whether the applicant was an insider or an outsider; that outsiders are just as rent-burdened as insiders (see sidebar); that the City itself admitted that the policy was irrelevant to most types of displacement (including all imminent displacement and all displacement from the City as a whole), and that there were no data available that could actually show how many at-risk insiders were helped and how many at-risk outsiders were hurt by the policy.

He also ignored the fact that the citywide applicant pool is disproportionately Black and Hispanic, so that it is members of those groups who were disproportionately hurt by a policy that limited more than 90 percent of the applicants to no more than 50 percent of the apartments.

He also ignored the fact that most applicants applied outside of their community districts most of the time (see sidebar).

Could his approach be successful, or is he just pandering?

It was anticipated that, sooner or later, New York City might have a leader who wanted to return to the old system. As such, the consent decree (its paragraph 20, as referenced in more detail in the annotations below) explicitly ruled out modifications based on the kinds of rationales that Cuomo has advanced. (The City waived the right to seek such modifications.)

It could be that Cuomo weighed in on a resolved, nine-year litigation that has already cost the City millions of dollars without understanding what the court order said. Alternatively, he knows that there is not a way to bring back more preference but decided that it was worthwhile to try to earn political points by arguing for a policy that divided New Yorkers into favored and disfavored classes.

- 1.

The decree is styled as a “Stipulation and Order of Settlement and Dismissal,” but the law is clear that, regardless of name, a court order that contains an injunction, as this one does, is, as a practical matter, a consent decree.

The proposal from former Governor Cuomo to “reestablish” New York City’s outsider-restriction policy in affordable-housing lotteries is taking verbatim from his recently released policy paper, “Addressing New York’s Housing Crisis,” at pages 19-20.

In all of strategies described above, extensive engagement with the community is essential. Development of any type often generates at least initial opposition. Because the community benefits from enhanced facilities from these types of developments – whether it involves libraries, recreational facilities or schools – it is easier to gain the consensus needed to move forward with these projects.

The ability to gain community support for affordable housing development received a significant setback in the 2024 legal settlement between New York City and affordable housing “advocates” in Winfield v. City of New York. The settlement phases out the longstanding “community preference” policy that reserved 50% of units in affordable housing lotteries for local residents. Although the settlement was framed as a step forward for racial equity and integration under the Fair Housing Act, in practice, the elimination of community preference will almost certainly disproportionately disadvantage the very low income communities of color where most affordable housing is actually being built.

The original rationale behind community preference was straightforward: in neighborhoods undergoing rapid development and rising rents, long-term residents—often Black, Latino, or Asian— should have a fair chance to benefit from new affordable housing before they are displaced. For decades, community preference has served as a stabilizing force, ensuring that families with deep roots in neighborhoods like East Harlem, Brownsville, or the South Bronx could access the very housing that their communities made possible through decades of disinvestment and resilience.

The settlement’s goal—to promote fair access to housing in all neighborhoods—is laudable. But without accompanying reforms to ensure more affordable housing is built in high opportunity, low-minority areas, the elimination of community preference is likely to become a purely symbolic victory. Most affordable housing in New York City continues to be built in historically disinvested communities of color, not in the predominantly White or affluent neighborhoods where integration is most lacking. Without a local preference, these new units will be opened up to citywide competition, diluting access for the very populations who are most vulnerable to displacement.

This creates a troubling paradox: in the name of fair housing, we may be making it harder for residents of low-income communities to obtain affordable housing in their own neighborhoods. A truly equitable housing policy must grapple with this reality. While eliminating barriers to entry into high-opportunity neighborhoods is necessary, it is not sufficient. Without real structural changes—such as rezoning exclusionary neighborhoods, expanding incentives for developers to build in affluent areas, and dramatically increasing the supply of affordable units outside the city’s core low-income districts—the promise of desegregation will remain unfulfilled.

Reopening the Winfield settlement to allow for the continued use of community preference —at least in neighborhoods where a disproportionate share of the city’s affordable housing is being built—would strike a more just balance. A revised policy could maintain local preference in these areas as a targeted anti-displacement measure, while requiring citywide access in neighborhoods that have historically excluded affordable housing altogether. In this way, the goals of integration and community stability need not be in conflict.

Fair housing should mean more than theoretical access—it should result in real, lived outcomes. For New York City’s low-income communities of color, that means ensuring they are not excluded from the very housing that is meant to serve them. Restoring community preference strategically and equitably would be a crucial step toward housing justice.